Sunday, February 27, 2005

Here's part of Valeriy Panyushkin's Feb. 25 column in Gazeta.ru (in Russian) - Russia Without Putin:

[...] And on the same day, the U.S. President Bush boasted that the Russian President Putin was losing the election in Moldova, and that Moldova was now on a path of democracy - the one pointed out by the United States.

And on the same day, the court in Strasbourg ruled that the war in Chechnya violated human rights, and now President Putin can no longer interrupt journalists at press conferences - like, who specifically is the person whose right have been violated, what's his last name and address? Here it is, in the materials of the Strasbourg Court!

And on the same day, Mikhail Kasyanov held a press conference, seemingly to announce the creation of a private consulting company, but in reality he announced that he would compete for the president's post in 2008.

Have they all conspired or what?!

And if that's not enough, Russia was also forced to lower the duty on foreign-made planes, and it became absolutely clear that the national airplane industry wasn't going to survive, and President Putin has lost support from major industrialists, who are convinced that, because of their inefficiency, I, a Russian citizen, have to fly on uncomfortable planes.

And if that's not enough, Aslan Maskhadov also offered a truce plan, and the soldiers' mothers did go for talks with Akhmed Zakayev after all.

And you know what I think it means? I think it means Russia has begun to live apart from President Vladimir Putin and apart from the vertical of power constructed by President Vladimir Putin.

The empire-minded are building an empire by themselves - actually, two empires are being built, because the Kremlin administration is building its own man-eating empire, and Anatoliy Chubais is building a liberal one of his own, and it's not clear which one is more man-eating.

Soldiers' mothers are negotiating peace in Chechnya by themselves.

Liberals are uniting on their own, and not as it was intended but as it's supposed to be done.

The impression is that various groups and elites have set off a very serious power struggle - and each group is using methods of its own. And it's not clear who's going to win. And it's possible that someone totally horrible wins, or perhaps it'll be someone decent.

One thing is clear: all these groups are fighting among themselves not for President Vladimir Putin anymore. They are fighting as if President Vladimir Putin was no longer there. As if he's turned into a mere decoration and existed only because there had to be someone to host at the highest level all those high-ranking foreign guest who were coming to Russia in May to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the Victory.

Thank you, Another Misha, for the comment I totally agree with and for the link to the Washington Post piece!

As I wrote yesterday, this part of Kolesnikov's press conference question was easy to miss: "...as far as Russia is concerned, everything is clear more or less."

The Washington Post's Peter Baker did just that - he totally missed it:

Luckily, Baker didn't appear as clueless writing about the other guy who asked Bush a wrong question:

To paraphrase Kolesnikov, as far as Interfax is concerned, everything is more or less clear.

An editorial in the Washington Post, Soft on Mr. Putin, sounded more like the Kommersant's Kolesnikov than their own Peter Baker:

So here's what we've got:

Bush is soft on Putin, Kolesnikov is tough on Bush - according to the Washington Post.

The Washington Post is tough on both Bush and Kolesnikov.

Mikhail Kasyanov, according to the Washington Post, speaks the truth - while President Bush doesn't.

In a way, Mikhail Kasyanov sounds like Kolesnikov: "The country is on the wrong track" isn't too different from "as far as Russia is concerned, everything is clear more or less."

Kolesnikov, however, never held important positions in Russia's Ministry of Finance under Yeltsin, didn't spend four years as prime minister in Putin's government and isn't considered a potential candidate in the 2008 presidential election - unlike Mikhail Kasyanov.

Go figure.

As I wrote yesterday, this part of Kolesnikov's press conference question was easy to miss: "...as far as Russia is concerned, everything is clear more or less."

The Washington Post's Peter Baker did just that - he totally missed it:

Although some print media in Russia remain lively and critical of the government, coming to Putin's defense at yesterday's news conference in Slovakia were two reporters who belong to the Kremlin press pool. The first was Andrei Kolesnikov, a correspondent for Kommersant, a business newspaper owned by Putin critic Boris Berezovsky. But Kolesnikov just released two books about his time covering Putin that the Kremlin likes.

Kolesnikov challenged Bush, asserting that "it's impossible to call Russia or the U.S. fully democratic" and questioned Bush about the "enormous powers of the security services" in the United States that had resulted in "the private lives of citizens falling under the control of the government."

Luckily, Baker didn't appear as clueless writing about the other guy who asked Bush a wrong question:

The second reporter, who questioned Bush's assertion that Russian media are not free, works for Interfax, a news service that often closely hews the state line.

To paraphrase Kolesnikov, as far as Interfax is concerned, everything is more or less clear.

An editorial in the Washington Post, Soft on Mr. Putin, sounded more like the Kommersant's Kolesnikov than their own Peter Baker:

The low point of President Bush's generally successful tour of Europe came at his news conference Thursday with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Fresh from a private discussion in which he said he raised such issues as the rule of law, free press and respect for political opposition, Mr. Bush issued what sounded like an endorsement of Mr. Putin's handling of "a country that is in transformation." Lauding the Russian ruler as a man who means what he says, Mr. Bush declared that "the most important statement . . . was the president's statement when he declared his absolute support for democracy in Russia."

[...]

The United States has pragmatic interests in cooperating with Russia on issues such as nuclear proliferation and the weapons programs of Iran and North Korea, and so Mr. Bush has good reason to avoid a rupture with a leader who has concentrated most political power in his own hands and is likely to remain in office until at least 2008. Yet it shouldn't be necessary to give Mr. Putin the message that his declarations of commitment to democracy will be accepted at face value even if his practice is the opposite. Better to state the truth, as former Russian prime minister Mikhail Kasyanov did in Moscow the same day: "The direction has changed," he said of Russia's political developments. "It's not the right one. The country is on the wrong track."

So here's what we've got:

Bush is soft on Putin, Kolesnikov is tough on Bush - according to the Washington Post.

The Washington Post is tough on both Bush and Kolesnikov.

Mikhail Kasyanov, according to the Washington Post, speaks the truth - while President Bush doesn't.

In a way, Mikhail Kasyanov sounds like Kolesnikov: "The country is on the wrong track" isn't too different from "as far as Russia is concerned, everything is clear more or less."

Kolesnikov, however, never held important positions in Russia's Ministry of Finance under Yeltsin, didn't spend four years as prime minister in Putin's government and isn't considered a potential candidate in the 2008 presidential election - unlike Mikhail Kasyanov.

Go figure.

Saturday, February 26, 2005

Something I wanted to write about since Thursday night but kept getting distracted...

The transcript of the press conference following the meeting between Bush and Putin in Bratislava does not carry the names of the reporters who were asking the questions. One question, however, from Andrei Kolesnikov of the Kommersant Daily, turned out to be quite a highlight of the press conference, at least here in Russia, so here's more on it:

Somewhat wordy, and because of that, it's easy to miss the "as far as Russia is concerned, everything is clear more or less" part when reading the transcript. Watching it live, though, this little bit sounded so emphatic it made one want to cheer Kolesnikov - "Go, boy, go!" - and he did go all the way, and because of him, not because of the answers he received, the press conference was very worth watching.

But here're the answers - from Bush:

And from Putin:

Whaterver.

Here's Kolesnikov take on it, from his story in the Kommersant (in Russian) that I've already referred to in my previous post:

***

A bit on Andrei Kolesnikov: before becoming the Kommersant's Kremlin pool reporter, he co-authored Putin's biography (there's even an English translation), and, several months ago, a two-volume collection of his Kommersant stories was published in Russian, documenting the first four years of Putin's reign.

Here's part of a St. Petersburg Times' review of the collection:

Kolesnikov also reported on the Orange Revolution, from Kyiv, and here're the links to the two excerpts from one of his pieces that I posted here way back in November and December: the first one, dealing with the politics of the moment, translated by me, and the second one, dealing with the more interesting and immediate aspects of the revolution, translated wonderfully by Michael Subotin (aka Another Misha).

***

If nothing else, all this provides an awesome insight into what Russian journalism's like - or what it can be like when the right people - like Kolesnikov - get involved. (The rumor is, by the way, that the Kommersant may soon be forced to shut down...)

The transcript of the press conference following the meeting between Bush and Putin in Bratislava does not carry the names of the reporters who were asking the questions. One question, however, from Andrei Kolesnikov of the Kommersant Daily, turned out to be quite a highlight of the press conference, at least here in Russia, so here's more on it:

QUESTION (THROUGH TRANSLATOR): First of all, I wanted to ask another question, but we have an interesting conversation now, therefore I'm going to ask about the following.

It seems to me that you have nothing to disagree about. The regimes in place in Russia and the U.S. cannot be considered fully democratic, especially when compared to some other countries of Europe, for example; for example, the Netherlands.

It seems to me that, as far as Russia is concerned, everything is clear more or less. But as far as the U.S. is concerned, we could probably talk at length.

I'm referring to the great powers that have been assumed by the security services due to which the private lives of citizens are now being monitored by the state.

This could be explained away by the consequences of September 11th, but this has nothing to do with democratic values.

How could you comment on this?

I suggest that you can probably agree, that you can probably shake hands and continue to be friends in future.

Somewhat wordy, and because of that, it's easy to miss the "as far as Russia is concerned, everything is clear more or less" part when reading the transcript. Watching it live, though, this little bit sounded so emphatic it made one want to cheer Kolesnikov - "Go, boy, go!" - and he did go all the way, and because of him, not because of the answers he received, the press conference was very worth watching.

But here're the answers - from Bush:

BUSH: I live in a transparent country. I live in a country where decisions made by government are wide open and people are able to call people to me to account, which many out here do on a regular basis.

Our laws and the reasons why we have laws on the books are perfectly explained to people. Every decision we have made is within the Constitution of the United States. We have a constitution that we uphold.

And if there's a question as to whether or not a law meets that constitution, we have an independent court system through which that law is reviewed.

So I'm perfectly comfortable in telling you, our country is one that safeguards human rights and human dignity, and we resolve our disputes in a peaceful way.

And from Putin:

PUTIN (THROUGH TRANSLATOR): I'd like to support my American counterpart. I'm absolutely confident that democracy is not anarchy. It is not a possibility to do anything you want. It is not the possibility for anyone to rob your own people.

Democracy is, among other things, and first and foremost, the possibility to democratically make democratic laws and the capability of the state to enforce those laws.

You have cited a curious example, the Netherlands. The Netherlands is a monarchy, after all. I have no doubts about the democratic nature of that country.

It is certainly a democratic nation, but this is very different from the United States and Russia. There are great differences between Russia and the U.S. as well.

If we talk about whether we have more or whether we have less democracy is not the right thing to do. But if we talk about how the fundamental principles of democracy are implemented in this or that historic soil, in this or that country, is an option -- it's possible. This does not compromise the dignity of the Netherlands or Russia or the U.S.

Whaterver.

Here's Kolesnikov take on it, from his story in the Kommersant (in Russian) that I've already referred to in my previous post:

Perhaps, I should've asked about cooperation in Iran and Iraq. There might have been people in the conference room who were counting on it. But a conversation on the fate of democracy was taking place, and it would've been silly to interrupt it halfway through. I said that, in my opinion, the two president had much in common: the regimes in both countries cannot be called democratic (especially compared to certain European countries - the Netherlands, for example). Regarding Russia, said I, everything is clear, and regarding the United States, one could talk about the increased influence the special services have on people's private lives. Yes, it started after September 11, but does it have anything to do with democracy?

In the end, I offered the presidents to agree with all this, shake each other's hands and continue being friends.

It wasn't modest of me. But to justify myself, I'd like to say that no one was particularly modest during this press conference.

For some reason, the presidents didn't agree. Mr. Bush even tried to interrupt me a few times, hinting with his gestures that he understood everything already.

He explained that America has given its people and the peoples of the world the main thing, freedom and democratic laws, which sustain this freedom.

"Our country is a democratic one," he declared.

It can't be said, though, that he has at least tried to answer the question.

Mr. Putin also didn't agree that there was something wrong with democracy in Russia.

"Democracy isn't anarchy," he declared, "isn't freedom to do all you want."

These words were painfully familiar.

According to Mr. Putin, the example of the Netherlands is an unusual one, but, actually, there's a monarchy over there.

In my view, though, what they've got in the Netherlands is democracy indeed - a democracy so well-developed that it can afford to keep the monarchy.

***

A bit on Andrei Kolesnikov: before becoming the Kommersant's Kremlin pool reporter, he co-authored Putin's biography (there's even an English translation), and, several months ago, a two-volume collection of his Kommersant stories was published in Russian, documenting the first four years of Putin's reign.

Here's part of a St. Petersburg Times' review of the collection:

The Kremlin has never expressed any displeasure at his frivolous reports, Kolesnikov said. Asked why he wasn't expelled from the Kremlin pool, he said, "If you don't lie, it's difficult to find a reason."

Kolesnikov said he disapproved of the decision to arrest Mikhail Khodorkovsky last year and switched from the more personal "Vladimir Putin" to the more formal "Mr. President" in his reports, which grew increasingly critical. He said the pro-Putin Moving Together youth movement approached him and demanded he drop the critical tone. He ignored the advice, he said.

"Putin's main mistake is that he thinks he knows what this country, its television and its governors should be like, and he's leading it down that path," Kolesnikov said. "I wish he were less sure in this regard."

Kolesnikov also reported on the Orange Revolution, from Kyiv, and here're the links to the two excerpts from one of his pieces that I posted here way back in November and December: the first one, dealing with the politics of the moment, translated by me, and the second one, dealing with the more interesting and immediate aspects of the revolution, translated wonderfully by Michael Subotin (aka Another Misha).

***

If nothing else, all this provides an awesome insight into what Russian journalism's like - or what it can be like when the right people - like Kolesnikov - get involved. (The rumor is, by the way, that the Kommersant may soon be forced to shut down...)

I'm slowly trying to recover the pictures that got lost today because fotopages.com suddenly and without warning decided to ban image hosting or whatever it's called. Maybe they didn't allow it from the very start but somehow I've been linking to my photos since September and it worked perfectly. Maybe I've exceeded some bandwidth limit or something - but I wasn't aware there was any, so it was a complete shock for me today when I saw all that fotopages.com advertising instead of my stuff... I'm still very grateful to those guys, though, and not really mad at them or anything - because I have over 2,300 photos there now, all for free, which is totally great.

I'm very, very grateful to Elya of the RomkaBlog for being my guardian angel when it comes to helping me fix the technical stuff. If it hadn't been for you, Elya, I would've spent a month not knowing where the problem came from. Thank you so much!

The blog is still going to look ugly for a while - until I finish moving the photos to PhotoBucket.com, a free image hosting place. Hope I'll manage to get it done sometime...

I'm very, very grateful to Elya of the RomkaBlog for being my guardian angel when it comes to helping me fix the technical stuff. If it hadn't been for you, Elya, I would've spent a month not knowing where the problem came from. Thank you so much!

The blog is still going to look ugly for a while - until I finish moving the photos to PhotoBucket.com, a free image hosting place. Hope I'll manage to get it done sometime...

Friday, February 25, 2005

Originally, I learned about it from Andrei Kolesnikov's today's piece in the Kommersant Daily (in Russian):

Here's the map (the image via This Blog will be Deleted by Tomorrow):

Here're a few bloggers' reations:

- The Glory of Carniola:

- Registan.net:

- Bratislava Blogging:

Here's the reaction from the Slovak Spectator - a follow-up on the We're on the map! piece, in a way...

He arrived in Bratislava the previous evening. The Slovak Spectator newspaper had this P1 headline on the eve of his visit: "We're on the Map!" The problem was, according to the Slovaks, that they were constantly being confused with the Slovenians. This meeting had to put everything where it belonged.

But it ended sadly. On the day of Mr. Bush's arrival, the USA Today published a map of Europe, on which a fat line outlined the country Mr. Bush was going to to meet with Mr. Putin. Alas, it was Slovenia. A Slovak journalist was walking around the international press center with this map, silently showing it to her colleagues. She couldn't speak. She had tears in her eyes.

Here's the map (the image via This Blog will be Deleted by Tomorrow):

Here're a few bloggers' reations:

- The Glory of Carniola:

Bush's Visit to Slovakia Takes a Detour

Folks, is it really so hard? I mean, I have to pause too sometimes and think about which country is Latvia and which one is Lithuania, or which one is Kyrgyzstan and how to spell it. But... if I had to prepare a map for a newspaper, I think I would find the five seconds necessary to just google it and make sure. Doing an image search for "Slovakia map" takes 0.15 seconds and gives you everything you need to know, including the important fact that it's not Slovenia. [...]

- Registan.net:

Important Announcement

Please update your European maps. Slovakia has moved. Not too far, just a little down and to the left, but they’re sure you’ll enjoy the new digs.

- Bratislava Blogging:

Slovakia has got a coastline!!

Here's the reaction from the Slovak Spectator - a follow-up on the We're on the map! piece, in a way...

US confusion over Slovakia

One of the leading US dailies, USA Today, published a map supposedly showing President Bush's route on his current tour of Europe, according to the daily SME.

But once again, Slovakia was mistaken for Slovenia.

During the 2000 American election campaign President Bush himself confused the two countries.

USA Today published the map in its edition on Monday, February 21.

It soon sparked an email joke reacting to the error.

President Bush was portrayed at the airport of the Slovenian capital, Ljubljana, wondering: "So, I come to visit them and there's nobody waiting for me?"

I haven't been here for a while, and today I see that this blog looks horrible again - all the pictures and other thingies that I store at my main and auxiliary fotopages refuse to load, even though everything looks normal when I go to those pages.

I've no idea why this happened and hope it gets fixed somehow soon... Nothing's more frustrating that those little technical things I've no control over...

I've no idea why this happened and hope it gets fixed somehow soon... Nothing's more frustrating that those little technical things I've no control over...

Wednesday, February 23, 2005

The news of all the "special operations" in Chechnya.

The news of all the raids on the shabby, 5-storeyed khrushchevka buildings in the neighboring republics.

In Khasavyurt, Daghestan, today, blood on the floor of a tiny, shitty apartment with shattered windows and bullet marks on the ceiling. The blood is, possibly, of Raja Aliyev, b. 1984, allegedly head of a militant group from Chechnya. A dead body on the floor is probably Aliyev's as well. On the table, "the evidence": a few Qur'ans and a dozen other religious-looking volumes - and then, suddenly, a 1980s Soviet edition of the Arabian Nights, its cover filled with Islamic ornaments, pretty and so unmistakably familiar. But I'm sure there are people out there who'd think it's yet another "fundamentalist" text. Also, there's a knife on the table that looks like something out of an antiques store or a bootlegger's backpack. No kitchen knives presented as "evidence" - which is very encouraging. Nothing that looks 100 percent like weapons, either, just the books - which is frightening.

Elsewhere in Russia, a very young man, missing both of his arms. There are the shoulders - and then nothing. He's a former soldier and he's at a hospital, where there are quite a few young men like him, crippled beyond hope. Many of them served in Chechnya. The young man can walk but there's no way he can take a leak without external help. A woman from a nearby church comes to the hospital regularly to sit and talk with these boys. The church community has collected money and bought several cell phones for the boys, so that they could call their relatives.

All this, on the NTV's 10 pm news program.

As David McDuff pointed out in his comment to the previous post, the Chechens mark the 61st anniversary of Stalin's deportations tomorrow (today). For the rest of the country, it's the Day of the Defenders of the Motherland, a day off.

The news of all the raids on the shabby, 5-storeyed khrushchevka buildings in the neighboring republics.

In Khasavyurt, Daghestan, today, blood on the floor of a tiny, shitty apartment with shattered windows and bullet marks on the ceiling. The blood is, possibly, of Raja Aliyev, b. 1984, allegedly head of a militant group from Chechnya. A dead body on the floor is probably Aliyev's as well. On the table, "the evidence": a few Qur'ans and a dozen other religious-looking volumes - and then, suddenly, a 1980s Soviet edition of the Arabian Nights, its cover filled with Islamic ornaments, pretty and so unmistakably familiar. But I'm sure there are people out there who'd think it's yet another "fundamentalist" text. Also, there's a knife on the table that looks like something out of an antiques store or a bootlegger's backpack. No kitchen knives presented as "evidence" - which is very encouraging. Nothing that looks 100 percent like weapons, either, just the books - which is frightening.

Elsewhere in Russia, a very young man, missing both of his arms. There are the shoulders - and then nothing. He's a former soldier and he's at a hospital, where there are quite a few young men like him, crippled beyond hope. Many of them served in Chechnya. The young man can walk but there's no way he can take a leak without external help. A woman from a nearby church comes to the hospital regularly to sit and talk with these boys. The church community has collected money and bought several cell phones for the boys, so that they could call their relatives.

All this, on the NTV's 10 pm news program.

As David McDuff pointed out in his comment to the previous post, the Chechens mark the 61st anniversary of Stalin's deportations tomorrow (today). For the rest of the country, it's the Day of the Defenders of the Motherland, a day off.

Tuesday, February 22, 2005

Some of it or nothing at all:

Perhaps, I should've kept silent about yesterday's sorry typo in a New York Times piece on Bush's visit to Europe - the paragraph, in which Yushchenko's name was spelled as "Yushenchenko," is now gone completely, together with any mention of Ukraine.

The way that paragraph described our election saga was awesome, too: "Mr. Putin also actively opposed the pro-Western candidacy of the Ukrainian presidential candidate, Viktor A. Yushenchenko [sic], who was ultimately sworn into office."

It reminded me of Putin's famous answer to Larry King's question about what happened to the Kursk submarine: "It sank," he said.

***

Although the piece is titled Bush Calls on Russia to Renew Commitment to Democracy (or, in today's edition, Bush Says Russia Must Make Good on Democracy), its focus isn't as pointed as that of the headlines: in the piece itself, Russia gets just a few paragraphs while the rest deals with other European matters.

Here's the Russia part, minus the paragraph on Ukraine:

***

Speaking about the free press in Russia, Izvestia, one of the leading Russian dailies, will now carry a New York Times English-language digest edition every Monday. The new project was launched yesterday.

Sadly, Izvestia's previous editor, Raf Shakirov, was forced to resign in September 2004, after devoting the whole P1 to a huge photo of the horror in Beslan.

Which doesn't mean it's not totally cool to have access to the New York Times' print edition from now on, digest or not. It is way cool.

Perhaps, I should've kept silent about yesterday's sorry typo in a New York Times piece on Bush's visit to Europe - the paragraph, in which Yushchenko's name was spelled as "Yushenchenko," is now gone completely, together with any mention of Ukraine.

The way that paragraph described our election saga was awesome, too: "Mr. Putin also actively opposed the pro-Western candidacy of the Ukrainian presidential candidate, Viktor A. Yushenchenko [sic], who was ultimately sworn into office."

It reminded me of Putin's famous answer to Larry King's question about what happened to the Kursk submarine: "It sank," he said.

***

Although the piece is titled Bush Calls on Russia to Renew Commitment to Democracy (or, in today's edition, Bush Says Russia Must Make Good on Democracy), its focus isn't as pointed as that of the headlines: in the piece itself, Russia gets just a few paragraphs while the rest deals with other European matters.

Here's the Russia part, minus the paragraph on Ukraine:

President Bush warned Russia today that it "must renew a commitment to democracy and the rule of law," but he said he believed the nation's future lies "within the family of Europe and the trans-Atlantic community."

The president's words, delivered in a major speech on American and European relations at the start of a four-day trip to Belgium, Germany and Slovakia, were his toughest yet about President Vladimir V. Putin's rollback of democratic reforms and crackdown on dissent in Russia. Mr. Bush is to meet with Mr. Putin on Thursday in Bratislava, Slovakia.

"We recognize that reform will not happen overnight," Mr. Bush said in the grand setting of Concert Noble, a 19th century hall. "We must always remind Russia, however, that our alliance stands for a free press, a vital opposition, the sharing of power and the rule of law - and the United States and all European countries should place democratic reform at the heart of their dialogue with Russia."

***

Speaking about the free press in Russia, Izvestia, one of the leading Russian dailies, will now carry a New York Times English-language digest edition every Monday. The new project was launched yesterday.

Sadly, Izvestia's previous editor, Raf Shakirov, was forced to resign in September 2004, after devoting the whole P1 to a huge photo of the horror in Beslan.

Which doesn't mean it's not totally cool to have access to the New York Times' print edition from now on, digest or not. It is way cool.

Lesya Malskaya has a website now: Malskaya.com.

It's a cool site, but I have a dial-up connection, and it was quite a pain for me to wait for all the pictures to load - I would have rather spent some more time at the actual exhibition...

It's a cool site, but I have a dial-up connection, and it was quite a pain for me to wait for all the pictures to load - I would have rather spent some more time at the actual exhibition...

They all heard it wrong - or did they?

Ukrainska Pravda reported Feb. 18:

The General Prosecutor's Office explained the real meaning of Pyskun's words to Abdymok:

Ukrainska Pravda reported Feb. 18:

[Prosecutor General Piskun] has informed about the creation of a special Gongadze murder inquiry fund, which might provide 5 million hryvnias to aid the investigation.

The General Prosecutor's Office explained the real meaning of Pyskun's words to Abdymok:

called the pgo to about the $1 million reward allegedly offered by pyskun on feb. 17.

the press office explained that pyskun, in fact, was referring to a prize offered by the all-ukrainian anti-corruption forum on july 12, 2002.

Monday, February 21, 2005

Reading this New York Times piece - Bush Calls on Russia to Renew Commitment to Democracy, by Elisabeth Bumiller - you'd think those November-December 2004 protests never actually took place and Ukraine is still one of those obscure, backstage countries, ruled by people with unfathomable names:

Russia has come under increasing criticism for what other nations see as a growing move toward power being concentrated in the hands of President Vladimir V. Putin, including control of the Russian news media. Mr. Putin also actively opposed the pro-Western candidacy of the Ukrainian presidential candidate, Viktor A. Yushenchenko [sic], who was ultimately sworn into office.

Today I had an urge to escape to Sarajevo for a few days sometime next week, but I didn't know whether Ukrainians require visas to enter Bosnia and Herzegovina.

I went to the site of Ukraine's Foreign Ministry and found the address of the Bosnian embassy - turned out it's in Moscow, not in Kyiv, on Mosfilmovskaya, very near to where I went to school here during the Chernobyl year (I even remember a Yugoslav girl attending the same school, though not her name - she was a few years my junior, her parents worked at the embassy).

I thought it was strange that Bosnia still didn't have an embassy in Ukraine, but I wasn't really curious about the reasons and was actually glad - because if the visa procedures were more complicated than those in Turkey (five minutes and $20 at the airport - perfect!), then at least I could skip going to Kyiv: what I wanted was an instant, relatively spontaneous, problem-less getaway.

I called the number listed on our Foreign Ministry page, and a woman there told me, in Russian, that I had to call the Consular Section. I called the number she gave me and was greeted in Bosnian, by another woman - who sounded middle-aged and very cozy.

At first, I thought it was my accent that prompted her to reply in her native language instead of Russian. But she went on explaining the visa procedures to me in Bosnian, and I realized that she just didn't speak Russian.

I understood much of it but not all. The funny thing was that I automatically switched from Russian to Ukrainian - just couldn't help it somehow. I wonder if the woman was aware of it.

From what she was saying, I realized I'd have to postpone my visit to Sarajevo - too many papers need to be assembled, unfortunately.

But I did spend some time asking questions and listening to her answers - I totally loved this weird but wonderful way of communication: me in Ukrainian, she in Bosnian. I didn't think it was unprofessional of her, or rude - no! A little eccentric? Yes. But she was very diligent in providing me with all the details, and she was very friendly.

In a way, it was a challenge for me - how much would I be able to understand? - and it reminded me of my interaction with a Belarusian opposition leader at the camp city in Kyiv back in December.

I loved the sound of Bosnian, by the way - and, funny, but that eases the pain of having to forget about my spontaneous trip to Sarajevo...

I went to the site of Ukraine's Foreign Ministry and found the address of the Bosnian embassy - turned out it's in Moscow, not in Kyiv, on Mosfilmovskaya, very near to where I went to school here during the Chernobyl year (I even remember a Yugoslav girl attending the same school, though not her name - she was a few years my junior, her parents worked at the embassy).

I thought it was strange that Bosnia still didn't have an embassy in Ukraine, but I wasn't really curious about the reasons and was actually glad - because if the visa procedures were more complicated than those in Turkey (five minutes and $20 at the airport - perfect!), then at least I could skip going to Kyiv: what I wanted was an instant, relatively spontaneous, problem-less getaway.

I called the number listed on our Foreign Ministry page, and a woman there told me, in Russian, that I had to call the Consular Section. I called the number she gave me and was greeted in Bosnian, by another woman - who sounded middle-aged and very cozy.

At first, I thought it was my accent that prompted her to reply in her native language instead of Russian. But she went on explaining the visa procedures to me in Bosnian, and I realized that she just didn't speak Russian.

I understood much of it but not all. The funny thing was that I automatically switched from Russian to Ukrainian - just couldn't help it somehow. I wonder if the woman was aware of it.

From what she was saying, I realized I'd have to postpone my visit to Sarajevo - too many papers need to be assembled, unfortunately.

But I did spend some time asking questions and listening to her answers - I totally loved this weird but wonderful way of communication: me in Ukrainian, she in Bosnian. I didn't think it was unprofessional of her, or rude - no! A little eccentric? Yes. But she was very diligent in providing me with all the details, and she was very friendly.

In a way, it was a challenge for me - how much would I be able to understand? - and it reminded me of my interaction with a Belarusian opposition leader at the camp city in Kyiv back in December.

I loved the sound of Bosnian, by the way - and, funny, but that eases the pain of having to forget about my spontaneous trip to Sarajevo...

As I wrote back in December, Tatyana Korobova's style isn't the easiest to get used to - but she does talk sense more often than not.

Here's a rough translation of part of her most recent piece in Obozrevatel (in Russian):

Korobova is also maddened by Internal Affairs Minister Lutsenko's approach to solving Georgiy Gongadze's murder - only I won't translate it here because Abdymok said it all four days ago, and here's a quote from him:

Just one final touch on this from Korobova:

Here's a rough translation of part of her most recent piece in Obozrevatel (in Russian):

But the motivations that led [Justice] Minister [Roman] Zvarych not to participate in the preparation of the Cabinet of Minister's ban on re-export of oil and to be the only one to vote against it should in no way and under no circumstances be considered as something shaped by the pure concern for the state (even if this indeed was so) - because the real reason the public scandal broke out was his wife, a deputy executive of the Oil Transit company, which was having problems with re-export of significant amounts of oil, and thus it was Minister Zvarych's personal interest - the only objective fact in this story, devoid of any ambiguity, unconditional and straightforward.

And this, I think, should have been guiding the President. And he should have proclaimed, "Damn, a justice minister (!!!) publicly threatening to resign because of a failed family oil contract is one thing I need in this bedlam!" - and then he should have told Zvarych to go to hell, satisfying his proud and principled request. And only after that he should have carried out an inquiry into the details of the Cabinet of Ministers' unanimous decision to ban re-export, and determined the pureness of everyone's intentions, and also untangled the specific case of Oil Transit, and, if necessary, kicked the asses of those who deserved it - publicly.

And it would have been correct to show the whole officialdom and all the people the absolute seriousness of the President's intentions to divorce business from the government - by downgrading Minister Zvarych to just Zvarych. [...]

Korobova is also maddened by Internal Affairs Minister Lutsenko's approach to solving Georgiy Gongadze's murder - only I won't translate it here because Abdymok said it all four days ago, and here's a quote from him:

complicating the situation is chief electrican lutsenko, who on feb. 17 pledged to grant immunity from prosecution and amnesty to policemen involved in trailing gongadze in july and September 2000.

by lutsenko’s logic, amnesty will also be granted to the thugs who smuggled dioxin into ukraine and mixed in yushchenko's champagne.

we all know, and even reported, the identities of those who trailed gongadze and yeltsov in 2000. several have been debriefed by the gpo, and their so-called testimony is available in the gallery here.

yushchenko’s unpredictable will and the new zeal of his willing accomplices are not bound by rule of law or the constitution.

Just one final touch on this from Korobova:

Well, Kuchma would be such a fool if he ignores the call: he did not kill "directly," he does have all the information - so why shouldn't he get all the "immunity guarantees" from Lutsenko, and 5 million hryvnias from Piskun, and then go on living openly, as a hero who has done a personal favor to a power duet, in which both guys have their own reasons to be catapulted out of their chairs and so, through their bullshitting, they are turning the "Gongadze case" into their personal parachute.

Saturday, February 19, 2005

One of those perfect moments that I rarely notice but wish they could last forever:

The church bells are ringing somewhere around the corner, very close; a dog is barking loudly down in the street; it's not completely dark yet, but the huge building on Krasnaya Presnya is already lit up; the constant hum of the distant Garden Ring traffic becomes audible again when the church bells stop.

The church bells are ringing somewhere around the corner, very close; a dog is barking loudly down in the street; it's not completely dark yet, but the huge building on Krasnaya Presnya is already lit up; the constant hum of the distant Garden Ring traffic becomes audible again when the church bells stop.

I've just posted 65 photos from yesterday's party at the farmers market - maybe it's a bit too much but I love every single photo I took there...

I don't want to promise anything, but maybe I'll write a little bit more about the market and the party later.

I don't want to promise anything, but maybe I'll write a little bit more about the market and the party later.

Today was the best day ever for me in Moscow.

The best.

!!!!!!!!!

Bolshoi Gorod, a wonderful Russian-language Moscow bi-weekly edited by Aleksei Kazakov and Masha Gessen, had a terrific party at Dorogomilovskiy Rynok - which was a follow-up on a photo story they did for their second issue since the re-design (in Russian, but do look at the photos!).

I ended up meeting a few dozen people - from Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Daghestan and maybe someplace else - and taking some 70 pictures of my own...

I'll try to post them all tomorrow.

(Boy, was it fun...)

Or maybe I'll cook plov instead, using the spices that one of the boys has magically assembled for me...

(I really don't think Kyiv was the right place for me to be born in. If not Central Asia or the Caucasus, I'd have preferred to be from the former Yugoslavia, at least...)

The best.

!!!!!!!!!

Bolshoi Gorod, a wonderful Russian-language Moscow bi-weekly edited by Aleksei Kazakov and Masha Gessen, had a terrific party at Dorogomilovskiy Rynok - which was a follow-up on a photo story they did for their second issue since the re-design (in Russian, but do look at the photos!).

I ended up meeting a few dozen people - from Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Daghestan and maybe someplace else - and taking some 70 pictures of my own...

I'll try to post them all tomorrow.

(Boy, was it fun...)

Or maybe I'll cook plov instead, using the spices that one of the boys has magically assembled for me...

(I really don't think Kyiv was the right place for me to be born in. If not Central Asia or the Caucasus, I'd have preferred to be from the former Yugoslavia, at least...)

Friday, February 18, 2005

Khatchig Mouradian has just left a comment to an entry on Orhan Pamuk's Snow - and since the entry is now hopelessly buried somewhere in the January archive, I'll quote the comment here (thank you, Khatchig!):

Dear Veronica Khokhlova,

I have read Orhan Pamuk's "Kar" (Snow) and Hitchens' review. I believe Pamuk is courageous enough. In a recent interview, he said: “30 thousand Kurds and 1 million Armenians were killed in Turkey. Almost no one dares speak but me, and the nationalists hate me for that” (The Swiss Tagesanzeiger, February 6).

Earlier, in an interview with the French weekly “L’Express” (13 December 2004), he was asked about the effects that the process of integration with the EU has on Turkey. Part of his answer was (I'm translating), “People have started little by little to speak, for example, about the Armenian question; whereas in the past, those who courageously went against this taboo were strongly attacked.”

Such declarations might be easy for me and you to make, but for someone like Pamuk, one of the icons of modern Turkey who lives in Istambul, these words can get one into a lot of trouble. Below is an example of what I mean:Charge Filed Against Writer Orhan Pamuk

Turkish Daily News

Feb 17 2005

Charges have been filed against internationally renowned Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk for statements he reportedly made during an interview with Swiss daily Tagesanzeiger, published in the newspaper's Feb. 6 issue, the Anatolia news agency reported.

Anatolia Professional Association of Owners of Scientific and Literary Works (ANASAM) President Mehmet Özer and attorney Mehmet Üçok filed the charges at the Kayseri Public Prosecutor's office.

Pamuk allegedly said in the interview that that 30,000 Kurds and 1 million Armenians had been killed in Turkey.

Thursday, February 17, 2005

I don't really understand anything about the justice minister's alleged desire to resign - but it seems that, just like anywhere else, it's all about oil.

Roman Zvarych said this on Channel 5 yesterday:

Roman Bezsmertny, vice prime minister, explained (in Ukrainian) at a news conference that the government had recently banned re-export of oil by Ukrainian companies, and Zvarych was against this decision.

Ukrainska Pravda explained (in Ukrainian) the situation by citing an open letter sent to Yulia Tymoshenko by Oil Transit, a company re-selling Russian oil to Slovakia and thus affected by the new ban. The letter describes some sort of a very complex scheme invented to bypass the ban (at least this is how I understand it). According to Ukrainska Pravda's unnamed sources, Roman Zvarych's wife works for Oil Transit (the company's name, in Ukrainian, is not googleable, somehow).

***

Even at the time of the 2002 parliamentary election, there was a tiny connection between Roman Zvarych and a trickle of oil (via The Jamestown Foundation):

***

I've no idea whether any of it has anything to do with the ordinary lives of ordinary Ukrainians. Reminds me of Russia: an oil-rich country where most people live in shit, more or less, and nothing can be done about it.

***

Abdymok has more on Zvarych and other recent developments/non-developments: here, here and here (the last one, about pigs, was very helpful in getting me back in touch with reality).

Roman Zvarych said this on Channel 5 yesterday:

I won't allow any businessmen, who are also Ukrainian parliament members and hold very powerful positions in the oil refinery sphere, to interfere directly in the work of my ministry. I also won’t allow the actions and decisions of certain members of the government to try getting members of my family involved in corrupt schemes.

Roman Bezsmertny, vice prime minister, explained (in Ukrainian) at a news conference that the government had recently banned re-export of oil by Ukrainian companies, and Zvarych was against this decision.

Ukrainska Pravda explained (in Ukrainian) the situation by citing an open letter sent to Yulia Tymoshenko by Oil Transit, a company re-selling Russian oil to Slovakia and thus affected by the new ban. The letter describes some sort of a very complex scheme invented to bypass the ban (at least this is how I understand it). According to Ukrainska Pravda's unnamed sources, Roman Zvarych's wife works for Oil Transit (the company's name, in Ukrainian, is not googleable, somehow).

***

Even at the time of the 2002 parliamentary election, there was a tiny connection between Roman Zvarych and a trickle of oil (via The Jamestown Foundation):

Late on the evening of March 29, the Vice Governor of West Ukraine's Ivano-Frankivsk Region, Mykola Shkriblyak was riddled with bullets on the stairs of his home. In the early hours of March 30, he died. His murder will have serious political consequences, he having been a favorite of the Verkhovna Rada (parliament) race in the local single-seat constituency and the leader of the Ivano-Frankivsk Regional branch of the United Social Democratic Party (USDP).

Until the election campaign got underway, Shkriblyak, as vice governor, supervised the lucrative energy sector in a region key to Ukraine's fuel industry. Ivano-Frankivsk is home to one of two western Ukrainian oil refineries--Nadvirna-based Naftokhimik Prykarpattya. Several Russian and Ukrainian companies have recently been vying for control of this plant, and Shkriblyak's position as broker was thus inherently dangerous.

President Leonid Kuchma personally instructed the prosecution, the police and secret services to solve the murder as soon as possible. The Ukrainian Prosecutor General's Office warned against anyone making hasty conclusions. Yet the Ivano-Frankivsk authorities hurried to define the murder as political, as did the USDP and For United Ukraine (the major pro-government force backing Shkriblyak in the parliamentary campaign). The Green Party said that it would withdraw its candidate from the constituency in protest. The same parties, along with front-running Viktor Yushchenko's Our Ukraine bloc, suggested that the election in the single-seat constituency Number 90 should be postponed until the murder is solved. But the election took place, and Shkriblyak's main rival--an American-born radical Ukrainian nationalist, Roman Zvarych--won.

Shkriblyak's tragic death has taken a toll on Our Ukraine, whose candidate Zvarych was. Moral scruples aside, USDP-linked media hinted that the party, or individuals connected to it, might be behind the murder. Inter, probably Ukraine's most popular television channel, showed in its evening news a video of Zvarych vowing to "tear his rivals to pieces" along with a report about Shkriblyak's murder. The message, aimed mainly at Russophone audiences in the East of Ukraine, where support for Yushchenko was thin, was clear. On April 1, the Kievskie Vedomosti newspaper claimed that the U.S. embassy had tried to help Zvarych. "Don't play with your fate," someone from the embassy told Shkriblyak, persuading him to bow out of the race, according to the newspaper. The embassy indignantly denied the allegation.

***

I've no idea whether any of it has anything to do with the ordinary lives of ordinary Ukrainians. Reminds me of Russia: an oil-rich country where most people live in shit, more or less, and nothing can be done about it.

***

Abdymok has more on Zvarych and other recent developments/non-developments: here, here and here (the last one, about pigs, was very helpful in getting me back in touch with reality).

I should never make any promises on this blog - because I never seem to keep them. You know, I'll write more about this and more about that - later - and I never do. Or, I'll visit Lesya Malskaya's photo exhibition at the Andrei Sakharov Center first thing next week - and then it takes me nearly two weeks to actually go there...

***

The Sakharov Center is located just off the (garden-less) Garden Ring - I walk five minutes through sludge and traffic from Kurskiy Train Station, then turn onto a narrow path trodden in the cleanest snow and end up in what seems like the remains of a charmed forest in the middle of a crazy megapolis. Even in summer, when today's contrast between the whiteness of the snow and the urban ugliness is no longer there, the place is still a bit too peaceful to really belong in Moscow.

I pass two modern art type of sculpture things - a Pegasus, and something that looks like a chunk of the Berlin Wall decorated with a huge hole and clumsy but colorful butterflies. I also pass a couple teenagers sitting on a bench, drinking beer, and a young mama with one hand on a baby carriage and the other holding a cigarette, her bottle of beer standing open in the snow next to her.

Then there's Sakharov's head on the wall, and the words beneath it: Andrei Sakharov, thank you!

Sad and beautiful.

The Center's got two buildings, and Lesya's exhibition is in the one with the following sign on it: Since 1994, there's a war going on in Chechnya. Enough!

It's a new sign that wasn't there the last time I visited the Center over three years ago - I was gathering some material on the Crimean Tatar movement then (the Center's got a really nice library in addition to the exhibition space, and, across the Garden Ring from it, there's the apartment where Sakharov used to live and which now houses his archives).

Inside, there's a guard dressed like a cop - he tells me to take off my coat and hang it in the wardrobe room myself, and that makes me feel at home.

I walk past the library (the door is open) and up the stairs. The staircase is decorated with a few orange flags and ribbons from Maidan.

Upstairs, the exhibition area is divided into three segments: one permanent exhibit of Gulag documents and another on Sakharov's life, and, squeezed in between, there are Lesya's Maidan photos, a Ukrainian flag and six TV screens playing scenes from the Orange Revolution and Yushchenko's inauguration.

There is no one but me there, and it upsets me at first, but the photos, and the Ukrainian anthem, and other Maidan sounds coming from the TV screens all make me feel as if I'm back in Kyiv, back in November, and then I catch myself smiling and humming the anthem to myself, and I end up spending a quarter of an hour walking back and forth, looking at the pictures and feeling totally happy.

Then a woman working at the Center brings in some visitors and tells me there's more stuff downstairs (blurry photos by Valeriy Rivan, in the hallway next to the Center's staff offices).

I tell her that I feel like I'm walking down some kind of a deja vu alley - and really enjoying it. She laughs - as if she knows exactly what I mean.

Lesya's photos are really great - though I wish there were more of them. Or, more exhibitions like hers. Here in Moscow - and everywhere.

She's now working on arranging an exhibiton in London and New York, and I hope it works out.

(A bunch of quick snapshots from my visit to the Sakharov Center is here.)

***

The Sakharov Center is located just off the (garden-less) Garden Ring - I walk five minutes through sludge and traffic from Kurskiy Train Station, then turn onto a narrow path trodden in the cleanest snow and end up in what seems like the remains of a charmed forest in the middle of a crazy megapolis. Even in summer, when today's contrast between the whiteness of the snow and the urban ugliness is no longer there, the place is still a bit too peaceful to really belong in Moscow.

I pass two modern art type of sculpture things - a Pegasus, and something that looks like a chunk of the Berlin Wall decorated with a huge hole and clumsy but colorful butterflies. I also pass a couple teenagers sitting on a bench, drinking beer, and a young mama with one hand on a baby carriage and the other holding a cigarette, her bottle of beer standing open in the snow next to her.

Then there's Sakharov's head on the wall, and the words beneath it: Andrei Sakharov, thank you!

Sad and beautiful.

The Center's got two buildings, and Lesya's exhibition is in the one with the following sign on it: Since 1994, there's a war going on in Chechnya. Enough!

It's a new sign that wasn't there the last time I visited the Center over three years ago - I was gathering some material on the Crimean Tatar movement then (the Center's got a really nice library in addition to the exhibition space, and, across the Garden Ring from it, there's the apartment where Sakharov used to live and which now houses his archives).

Inside, there's a guard dressed like a cop - he tells me to take off my coat and hang it in the wardrobe room myself, and that makes me feel at home.

I walk past the library (the door is open) and up the stairs. The staircase is decorated with a few orange flags and ribbons from Maidan.

Upstairs, the exhibition area is divided into three segments: one permanent exhibit of Gulag documents and another on Sakharov's life, and, squeezed in between, there are Lesya's Maidan photos, a Ukrainian flag and six TV screens playing scenes from the Orange Revolution and Yushchenko's inauguration.

There is no one but me there, and it upsets me at first, but the photos, and the Ukrainian anthem, and other Maidan sounds coming from the TV screens all make me feel as if I'm back in Kyiv, back in November, and then I catch myself smiling and humming the anthem to myself, and I end up spending a quarter of an hour walking back and forth, looking at the pictures and feeling totally happy.

Then a woman working at the Center brings in some visitors and tells me there's more stuff downstairs (blurry photos by Valeriy Rivan, in the hallway next to the Center's staff offices).

I tell her that I feel like I'm walking down some kind of a deja vu alley - and really enjoying it. She laughs - as if she knows exactly what I mean.

Lesya's photos are really great - though I wish there were more of them. Or, more exhibitions like hers. Here in Moscow - and everywhere.

She's now working on arranging an exhibiton in London and New York, and I hope it works out.

(A bunch of quick snapshots from my visit to the Sakharov Center is here.)

Wednesday, February 16, 2005

Went over to the Chicago Tribune to read a piece on blogging (via Instapundit), but couldn't really focus for too long on the musings about blogging vs journalism in the so foreign - British and U.S. - settings.

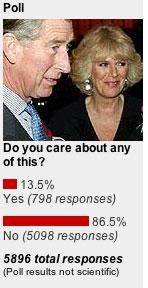

So I ended up answering a charming poll question stuck in the margin:

I don't care.

So I ended up answering a charming poll question stuck in the margin:

I don't care.

Tuesday, February 15, 2005

BBC's In Pictures showcases work of Simon Roberts, a British photographer - Postcards from Russia:

My favorite photo is that of a "Russian Alcoholic" - an amazing transformation of a gloomy, hopeless subject into an almost pretty one, and an example of how much can be achieved by switching from "trying to cover your natural and inescapable habitat" mode to the "working in the field" approach.

Photo: Simon Roberts

Caption: Kyakhta, Russia-Mongolia Border

A former stage post on the tea route from Shanghai to the Russian cities of Siberia, Kyakhta on the Russian-Mongolian border is now a heavily militarised border post.

Today the tea warehouses and factories have been abandoned and there is virtually no employment.

Husband and father, Sergei Shanzin, aged 24, does have a job but is an alcoholic. He asked that this photograph carry the caption "Russian Alcoholic."

***

The World Press Photo 2004 award winners were announced a few days ago.

Even though the image below didn't receive the World Press Photo of the Year 2004 title, I can't stop looking at it...

Photo: Shaul Schwarz, Israel, Corbis

Caption: Young boy looting, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 27 February

In August 2004, photographer Simon Roberts embarked on an ambitious twelve-month journey across Russia to document the reality of daily life outside of Moscow, photographing those people for whom the wealth of the capital is nothing more than a fantasy.

Told through personal stories of citizens living in this vast nation, his project aims to illustrate the wider issues affecting modern Russia.

We present a selection of his 'postcards from the field' halfway through his epic journey.

My favorite photo is that of a "Russian Alcoholic" - an amazing transformation of a gloomy, hopeless subject into an almost pretty one, and an example of how much can be achieved by switching from "trying to cover your natural and inescapable habitat" mode to the "working in the field" approach.

Photo: Simon Roberts

Caption: Kyakhta, Russia-Mongolia Border

A former stage post on the tea route from Shanghai to the Russian cities of Siberia, Kyakhta on the Russian-Mongolian border is now a heavily militarised border post.

Today the tea warehouses and factories have been abandoned and there is virtually no employment.

Husband and father, Sergei Shanzin, aged 24, does have a job but is an alcoholic. He asked that this photograph carry the caption "Russian Alcoholic."

***

The World Press Photo 2004 award winners were announced a few days ago.

Even though the image below didn't receive the World Press Photo of the Year 2004 title, I can't stop looking at it...

Photo: Shaul Schwarz, Israel, Corbis

Caption: Young boy looting, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 27 February

Monday, February 14, 2005

The main news from Ukraine - besides Yulia Tymoshenko and most of her ministers ice skating like little kids yesterday morning - is that Boris Nemtsov is now Yushchenko's adviser on Russian investments.

I used to be sort of mad at Nemtsov for losing the 2003 Russian Duma election so pathetically, and because of that, I didn't really like seeing him on Maidan. Now that we've won, I no longer have any hard feelings about him. I just hope his appointment is really going to be more about the economy than politics.

I used to be sort of mad at Nemtsov for losing the 2003 Russian Duma election so pathetically, and because of that, I didn't really like seeing him on Maidan. Now that we've won, I no longer have any hard feelings about him. I just hope his appointment is really going to be more about the economy than politics.

The weather's so dramatic here today: a snowstorm.

Wild.

I'm sitting on the window sill, on the ninth floor, watching the wind blow the snow off the neighboring rooftops. I'm reading Orhan Pamuk's Snow again and listening to Goran Bregovic.

The huge building on Krasnaya Presnya is just slightly visible now.

A wonderful day to stay home, cozy and warm.

Wild.

I'm sitting on the window sill, on the ninth floor, watching the wind blow the snow off the neighboring rooftops. I'm reading Orhan Pamuk's Snow again and listening to Goran Bregovic.

The huge building on Krasnaya Presnya is just slightly visible now.

A wonderful day to stay home, cozy and warm.

Friday, February 11, 2005

Some people see the Orange Revolution this way:

Not completely a revelation, but still a view one tends to forget about after a while.

This is the first major struggle between the US and the old remnants of the Soviet Union over an entire people since the end of the cold war. The old KGB operative vs. the architect of the War on Terror.

Not completely a revelation, but still a view one tends to forget about after a while.

merhabaturkey.com

Mike, our dearest friend and also the owner of the hotel we're always staying at in Istanbul, was once asked by an American guest:

- Why is it that all the trucks here have 'Mashallah' written on them? Is that the name of some Turkish insurance company or something?

After a barely noticeable pause, Mike grinned and replied:

- Hmm. Yeah. You may call it an insurance company. The biggest one out there.

tulumba.com

Thursday, February 10, 2005

Normally, I wouldn't write on something like this - but whenever stuff falls on me in batches, I can't just shrug it off...

I glanced through a Gazeta.ru item about a group of young men in St. Pete killing another young man today, with - of all things - axes. Someone saw them doing it and called the police, but it was too late. The man they killed, Andrei Silantyev, b. 1977, was a Mining Institute instructor.

Crime and punishment, I thought. And: I'm so happy I'm not in St. Pete anymore.

Within half an hour, I was looking through Blogrel, a blog about Armenia, and came upon an entry about Lt. Ramil Safarov, an Azeri, being tried in Hungary for the 2004 murder of Lt. Gurgen Margaryan, an Armenian. Both were attending the NATO-sponsored Partnership for Peace English Language program in Budapest and lived in the same dorm. One night, Safarov entered Margaryan's room and killed him with an axe.

There's a site about it, The Budapest Case, complete with the account of the murder, the history of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, the Azeri officials' responses to the case, the transcripts of Safarov's confession and Margaryan's roommate's testimony, and more.

Here's the axe part, from the gruesome and horribly translated confession transcript:

Some "partnership for peace" they got there...

I glanced through a Gazeta.ru item about a group of young men in St. Pete killing another young man today, with - of all things - axes. Someone saw them doing it and called the police, but it was too late. The man they killed, Andrei Silantyev, b. 1977, was a Mining Institute instructor.

Crime and punishment, I thought. And: I'm so happy I'm not in St. Pete anymore.

Within half an hour, I was looking through Blogrel, a blog about Armenia, and came upon an entry about Lt. Ramil Safarov, an Azeri, being tried in Hungary for the 2004 murder of Lt. Gurgen Margaryan, an Armenian. Both were attending the NATO-sponsored Partnership for Peace English Language program in Budapest and lived in the same dorm. One night, Safarov entered Margaryan's room and killed him with an axe.

There's a site about it, The Budapest Case, complete with the account of the murder, the history of the Armenian-Azerbaijani conflict, the Azeri officials' responses to the case, the transcripts of Safarov's confession and Margaryan's roommate's testimony, and more.

Here's the axe part, from the gruesome and horribly translated confession transcript:

For the question I would like to say that whole thing goes back to 1988 Armenian-Karabahi War, after which there was cease-fire, but nobody kept this cease-fire, but the very tragedy that I was talking about happened in 1992 February 26. At that time Armenian soldiers attacked the Karabki Hodzani* area, where were only civil citizens, particularly children and women and old people and around 8000 people were killed. This is my blood; I called them relatives in the future. Armenians occupied my place of birth for 1 year in 1993, August 25. This is also memorable as it happened on the date of my birth. I don’t know how many people were killed at that time, but even though it’s huge number. That was the time when I lost part of my close relatives as well. I applied to the army in 1991, this was a soldier secondary school, after 1 year I received further training in Turkey, where I received certificate (secondary and high education). The only motivation for me for fight against Armenians and to kill as many as possible in the fight. Me, as being azeri soldier, took weapon in order to protect my home, and there were other reasons as well, such as that after the collapse of the Soviet Union the army was destroyed and I felt that new army needs me.

[...]

My army sent me to this training and being here I have to face the fact that two Armenian were learning with me and I have to say that because of personal effectiveness the feeling of animosity grow up in me. In the beginning we were greeting each other, rather to say they said hi to me, but I didn’t accept it and curiosity in the whole thing was that when they walked close to me they were mumbled something in Armenian and laughed at me. That was the time when I decided that I will kill these two persons, the Armenians, I will cut their head off. The reason for this is that Armenians kill Azerbaijanians in the same way. What I already mentioned – the 8000 people carnage happened this way by Armenians. I didn’t plan the murder of the two Armenian at that day, but just at Ferbuary 26, taking into consideration an anniversary, but because of that laugh at me the feeling of animosity became bigger and bigger and that’s why I decided that that day in the morning I kill both of them. That’s why yesterday, at the 18th, around 19.00 I bought an axe near to Tesco at Nepstadion. I decided next to axe, because however I had a knife, I rather though I will not use that, because if I pierce them through by the knife, they may shout, shout for help, but if I hit their head by the axe, they loose their consciousness and will not be able to shout for help.

[...]

The handle of the axe was around 1 meter long and the iron part was red, color of the light tree.

[...]

After I bough the axe, after 19.00, I returned to my accommodation at Hungaria krt. At room number 219/A I was alone, because my room mate – Ukrainian soldier traveled home, because of the death of one of his relatives. I hide axe, the knife and the honing stone under my bed case. After this I did my English homework, I closed my door with key and starter to sharp, after that I went out to the hall to have a cigarette, in the bath. I was up till 5 a.m. and I haven’t slept at all and then I grabbed the axe and I put the knife into my right pocket. The reason for choosing this early time, because according to my knowledge this is the time, when sleeping is the deepest, when they do not wake up for small noise, and I also have to be sure the place where the person that I wanted to kill was sleeping, because his room mate is the Hungarian citizenship. I didn’t want to heart him, because he is really nice guy. [...]

Some "partnership for peace" they got there...

I was looking through my photo archive yesterday and found this photo: it was taken in early November 2003, a year before Khreshchatyk turned completely orange!

I was very surprised to see the picture, don't remember taking it - I just know that part of the reason I made this shot was because I love orange color, and also because of the Coca Cola thing right next to Yushchenko's (so brand new!) tent.

Who could have thought then that Yushchenko would indeed become our President...

I was very surprised to see the picture, don't remember taking it - I just know that part of the reason I made this shot was because I love orange color, and also because of the Coca Cola thing right next to Yushchenko's (so brand new!) tent.

Who could have thought then that Yushchenko would indeed become our President...

Wednesday, February 09, 2005

I've had this totally atypical housewifely encounter today.

Our washing machine was broken when we moved in, and I was really grateful when the repairman finally showed up: a couple more days, and I was facing Mishah's rebellion when he ran out of things to wear.

The repairman was short yet sturdy, a former PE teacher, originally from Kazakhstan. We chatted while he worked, about kids, sports, Ukrainian language, the Orange Revolution - and the relatively recent, failed, attempts to secede, undertaken by Kazakhstan's Russian Cossacks. The repairman had been one of the Cossack activists.

He called himself a "Russian Nationalist" (admitting, though, that he had some Ukrainian and Belarusian roots). He said he'd been jailed for his involvement in politics (back in Kazakhstan). He said that they'd been persecuted not by the Kazakh secret services - but by the Russian FSB. He said that the only people from Russia, the historic homeland, who'd had the guts to support them were Eduard Limonov's National Bolshevik Party guys. I said Limonov was making me sick, and the repairman said he disliked Limonov, too. He called himself a "political technologist" and was curious about my opinion on why the Orange Revolution succeeded. I said that the Yanukovych persona had played a great role - had they picked someone less obnoxious, many people would have prefered to stay home and watch TV, instead of going out to Maidan. He said he'd heard other people say the same thing, which meant it was true. He said he expected many bad things to happen in Ukraine in the near future (including bloodshed in Crimea) - but believed that Yushchenko was far better for Russia than Yanukovych would have been: because Yanukovych would have been demanding special treatment from Russia, free gas and all, but with Yushchenko, all Ukraine's future problems would be Ukraine's only, and Russia wouldn't be to blame for any of them. I said I'd heard it from other people, too, and completely agreed: Ukraine's problems are none of Russia's business, and it's good they are finally beginning to understand it.

All in all, the repairman wasn't a bad man. I gave him tea and chocolates when he was done with the washing machine; he bummed a cigarette from me. I paid him; he signed all the papers and gave me a discount card.

I googled his name after he left, just out of habit, not really expecting to find anything. But he was there, mentioned in quite a few nationalist sources. I don't think it'd be fair to disclose his identity any further than I've already done - after all, he told me at some point that everything that was being published on the Internet was "a gift for the CIA."

Well, just one more thing: the repairman is briefly mentioned in one of Eduard Limonov's books, The Anatomy of a Hero, posted on the NBP's site in full (in Russian). Back in 2001, the Russian authorities accused Limonov of "plotting a series of terror attacks and [...] an armed invasion of northern Kazakhstan, where they tried to recruit volunteers to carry out a plan entitled 'A Second Russia'." As a result, Limonov spent over two years in custody and in jail.

Our washing machine was broken when we moved in, and I was really grateful when the repairman finally showed up: a couple more days, and I was facing Mishah's rebellion when he ran out of things to wear.

The repairman was short yet sturdy, a former PE teacher, originally from Kazakhstan. We chatted while he worked, about kids, sports, Ukrainian language, the Orange Revolution - and the relatively recent, failed, attempts to secede, undertaken by Kazakhstan's Russian Cossacks. The repairman had been one of the Cossack activists.

He called himself a "Russian Nationalist" (admitting, though, that he had some Ukrainian and Belarusian roots). He said he'd been jailed for his involvement in politics (back in Kazakhstan). He said that they'd been persecuted not by the Kazakh secret services - but by the Russian FSB. He said that the only people from Russia, the historic homeland, who'd had the guts to support them were Eduard Limonov's National Bolshevik Party guys. I said Limonov was making me sick, and the repairman said he disliked Limonov, too. He called himself a "political technologist" and was curious about my opinion on why the Orange Revolution succeeded. I said that the Yanukovych persona had played a great role - had they picked someone less obnoxious, many people would have prefered to stay home and watch TV, instead of going out to Maidan. He said he'd heard other people say the same thing, which meant it was true. He said he expected many bad things to happen in Ukraine in the near future (including bloodshed in Crimea) - but believed that Yushchenko was far better for Russia than Yanukovych would have been: because Yanukovych would have been demanding special treatment from Russia, free gas and all, but with Yushchenko, all Ukraine's future problems would be Ukraine's only, and Russia wouldn't be to blame for any of them. I said I'd heard it from other people, too, and completely agreed: Ukraine's problems are none of Russia's business, and it's good they are finally beginning to understand it.

All in all, the repairman wasn't a bad man. I gave him tea and chocolates when he was done with the washing machine; he bummed a cigarette from me. I paid him; he signed all the papers and gave me a discount card.

I googled his name after he left, just out of habit, not really expecting to find anything. But he was there, mentioned in quite a few nationalist sources. I don't think it'd be fair to disclose his identity any further than I've already done - after all, he told me at some point that everything that was being published on the Internet was "a gift for the CIA."

Well, just one more thing: the repairman is briefly mentioned in one of Eduard Limonov's books, The Anatomy of a Hero, posted on the NBP's site in full (in Russian). Back in 2001, the Russian authorities accused Limonov of "plotting a series of terror attacks and [...] an armed invasion of northern Kazakhstan, where they tried to recruit volunteers to carry out a plan entitled 'A Second Russia'." As a result, Limonov spent over two years in custody and in jail.

Tuesday, February 08, 2005

Komsomolskaya Pravda has a tabloid-style story on Yulia Tymoshenko's childhood and student years (in Russian). She'd learned to read before she went to school, was a good student, had many friends and could be rather tough when it came to defending her friends' and her own interests, blah-blah-blah.

Here's a very sweet picture from her high school yearbook - her name was Yulia Grigyan then:

Here's a very sweet picture from her high school yearbook - her name was Yulia Grigyan then:

I'm slowly regaining interest in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict - thanks to Abu Mazen.

The New York Review of Books has a very informative feature on him - The Last Palestinian, by Hussein Agha and Robert Malley:

Hopefully, things will begin to improve soon.

The New York Review of Books has a very informative feature on him - The Last Palestinian, by Hussein Agha and Robert Malley:

Abu Mazen is a politician of conviction, which is to say, until recently, not much of a politician at all. His behavior is rarely scheming; it is, if anything, a pure outgrowth of his emotional and temperamental makeup, a feature that accounts for his many successes and not a few of his setbacks. Guided by a deep sense of ethics, repugnance for sheer political expediency, and an exaggerated faith in the power of reason, he will seldom give in or fight back when rebuffed or slighted. Convinced that he has logic and reason on his side, and equally convinced that logic and reason are the faculties that guide all others, he would much rather passively wait until in due course people see things his way. There is little of the manipulator, deceiver, or conspirator in him, which is perhaps why he is so unforgiving of the manipulations, deceptions, and conspiracies of others. [...]