I watched Tony Scott's "Man on Fire" in the middle of the night, Friday to Saturday night (don't ask me why - there're too many answers but none makes enough sense). In Russian, the film is called "Wrath" ("Gnev"), and though I wouldn't say that the Russian word necessarily implies vengeance, the English one does, and this is what the film is about. (Warning: spoilers ahead.)

It was horrible watching it - but I enjoyed it, in a masochistic way.

A relative fiction about one little, non-Mexican girl kidnapped somewhere in Mexico - and a vivid memory of a non-fictional kidnapping of several hundred non-Russian kids somewhere in Russia. The film is based on a true story, so it's only partly fiction - and a memory of something seen on TV isn't the actual experience, so, to most of us, Beslan is only partly non-fiction. Denzel Washington's revenge - the rescue of the girl - and his death at the end. An attempt to rescue the real kids - a total mess - and the real, irreversable death of too many of these real kids, and many of the adults. Bruce Willis in "Die Hard I" on an all-Russian, state-funded TV channel just several hours after the awful finale - Bruce Willis saving everyone - just like they all had been expecting him to do on Sept. 11 three years ago. Him or someone like him. Waiting for Putin to make some kind of a statement - thinking, with no real hope: what if he resigns?

I still can't believe they were showing "Die Hard" that night. "Man on Fire" would've been as inappropriate. Taking revenge instead of waiting for a hero. But revenge in real life never goes as smoothly as it does in Hollywood. It's never as beautiful and satisfying. Denzel Washington thought the girl was dead, this was his motivation for revenge - but she turned out to be alive. It's not like this in real life - those Beslan kids are dead, and their parents know it. Denzel Washington had the skills and the movie luck to hunt down and kick the shit out of the bad guys, causing no collateral damage. And just imagine what might happen after Oct. 13, when the 40-day mourning period ends in Beslan.

And still, on that night, I would've rather watched Denzel Washington's rage than Bruce Willis' heroics. Or none of it at all, not ever.

Saturday, September 25, 2004

Thursday, September 23, 2004

At the end of August, I sent two of my photos to the BBC News Online's photography competition, Photographer of the Year, and one of them was selected by their picture desk - and it's now posted in a picture gallery HERE.

The theme was Solitude, my photo is #6 of 12. I took it last year here in St. Pete, and the memory of this old woman is still breaking my heart.

There was a vote a few nights ago to select two winners in this category, and my picture didn't make it - but I'm so terribly happy about having been selected at all!!!!!!!!!

The theme was Solitude, my photo is #6 of 12. I took it last year here in St. Pete, and the memory of this old woman is still breaking my heart.

There was a vote a few nights ago to select two winners in this category, and my picture didn't make it - but I'm so terribly happy about having been selected at all!!!!!!!!!

AFTER BESLAN: NOTES ON THE COVERAGE (6)

The Valdai Discussion Club's website now has a compilation of articles published as the result of the Sept. 6 meeting with Putin. These so far include Susan B. Glasser's piece in The Washington Post; two of Jonathan Steele's Guardian stories that I have mentioned in the previous entries here; Fiona Hill's misleading op-ed in The New York Times that I've also examined a few days ago; two pieces by Mary Dejevsky of The Independent - one focusing on Putin's views on the situation in Chechnya, another providing a general overview of the meeting; a translation of Yevgenia M. Albats' exposé published in the Russian-language Yezhenedelny Zhurnal; and two analytical pieces by Simon Saradzhyan from The Moscow Times.

I've been planning to write about Yevgenia Albats text, but since it meant I'd have to translate extensively, I kept postponing it, out of laziness. I'm really glad that the hard part, the translation, has been done by someone else, Scott Stephens. I'm sure his translation is of a much higher quality than mine would have been - and I'm grateful to him.

I also feel that the Valdai Discussion Club folks deserve lots of credit for having re-published Albats' piece on their site; this is very courageous of them - because her piece, titled "The Kremlin Actively Recruits Western Experts to Improve Russia's Image," is very very critical of this whole endeavor and of the people who chose to participate in it.

Albats, a highly esteemed Russian journalist and member of the Center for Public Integrity's International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, tackles an issue that none of those who attended the conference and the meeting with Putin have so far chosen to focus much on: the money issue.

Comments provided to Albats by Mary Dejevsky of The Independent are quite telling, too:

However, there was indeed a non-free way to get access to Putin and other high-ranking Russian officials, according to Albats:

Obviously, Albats did not attend the conference and the meeting with Putin; allowing her in might have proved as detrimental to Russia's image as inviting Anna Politkovskaya, an outspoken Russian journalist who, allegedly, was poisoned on her way to Beslan, and thus prevented from covering the tragedy. According to Dejevsky, though, the real reason for leaving many of the local journalists out had to do with - ironically - money:

After I read Albats' piece, I was very curious about Dejevsky's post-Sept. 6 reports. But here the money issue struck again: I was too late to catch her stories while they were still available for free reading online. I looked for them on The Independent site, about a week ago, and the cheapest option for me was to pay "£1 for 24 hours' access to this article" - but I don't have a credit card and, even if I did, it'd still be such a waste, for why on earth would I need 24 hours to read a newspaper story? (The Valdai Discussion Club site has reprinted Dejevsky's stories not from The Independent but from The Belfast Telegraph - and this paper's options are significantly cheaper: they are asking just "50p for 24 hours' access to this article.")

In any case, I'm grateful to the Valdai Discussion Club people for giving me a chance to read two of Dejevsky's stories free of charge. One important thing that I've found out is that Putin didn't say he was prepared to violate the Russian Constitution in order to grant "maximum autonomy" to Chechnya, as Fiona Hill of the Brookings Institution wanted everyone to believe.

Here's what Dejevsky wrote on the issue in her first piece (Sept. 7):

While I find this oil revenue initiative interesting and will definitely look for more information on it, I still don't understand how all this endless talk about parliamentary election in Chechnya could be considered "an unexpected change of tone." And does Putin only "seem" to "extend an olive branch" - and if yes, how could it possibly be considered "a clear indication that he was open to the holding of parliamentary elections in Chechnya"? (Though I have to admit that, no matter how subjective Dejevsky's conclusions are, they are almost timid compared to the assertions Fiona Hill has made in her New York Times op-ed.)

In her Sept. 8 piece - "Evening of Surprises With a Hospitable President" - Dejevsky writes in great detail about the idyllic atmosphere of Putin's Novo-Ogaryovo residence and his great personal charm. All of this is, of course, sickeningly irrelevant to what had happened in Beslan just five days earlier. Actually, it's so sickening that I won't quote any of it here - I've provided the link to this piece at the beginning of this entry.

As for the confirmation of Fiona Hill's "maximum autonomy" comment - I haven't found it here, either. As in other sources, all Putin is quoted saying is this:

The Independent ran another post-Sept. 6 piece, which hasn't yet been posted on the Valdai Discussion Club site but is still somehow available free of charge: "Eyeball to Eyeball With Vladimir Putin" by John Kampfner, political editor of the New Statesman. In it, Kampfner treats Putin the way all presidents deserve to be treated: as politicians. This is the attitude that won't make Kampfner blush in the future:

This all sounds good. It's funny, though that the very next thing Kampfner chooses to allude to is, possibly, Yevgenia Albats' piece:

This is a good point, gracefully delivered, and, moreover, it doesn't contradict what Albats wrote about Mary Dejevsky: "...I cannot help mentioning that in contrast to Mary Dejevsky the reporter, Mary Dejevsky the columnist does not at all hide her sympathy for Russia's current leadership."

Kampfner's conclusions appear quite solid at first:

Kampfner is not "shouting from the rooftops" - but, unfortunately, he seems to be viewing the situation in Russia from as high up as a rooftop. If Beslan, and the Nord-Ost theater siege, and the numerous deadly explosions haven't been convincing enough, what else has to happen that would force Putin to reconsider some of his policies? On the other hand, there's a very sobering element in Kampfner's argument: if Russia is more dangerous to itself than it is to the West (which it sure is), then why does the West have to bother too much about getting involved? Even if we take the scary "domino effect" factor into account, isn't it more reasonable for the Russian citizens (including the Chechens and their neighbors) to try to get more involved first?

The Valdai Discussion Club's website now has a compilation of articles published as the result of the Sept. 6 meeting with Putin. These so far include Susan B. Glasser's piece in The Washington Post; two of Jonathan Steele's Guardian stories that I have mentioned in the previous entries here; Fiona Hill's misleading op-ed in The New York Times that I've also examined a few days ago; two pieces by Mary Dejevsky of The Independent - one focusing on Putin's views on the situation in Chechnya, another providing a general overview of the meeting; a translation of Yevgenia M. Albats' exposé published in the Russian-language Yezhenedelny Zhurnal; and two analytical pieces by Simon Saradzhyan from The Moscow Times.

I've been planning to write about Yevgenia Albats text, but since it meant I'd have to translate extensively, I kept postponing it, out of laziness. I'm really glad that the hard part, the translation, has been done by someone else, Scott Stephens. I'm sure his translation is of a much higher quality than mine would have been - and I'm grateful to him.

I also feel that the Valdai Discussion Club folks deserve lots of credit for having re-published Albats' piece on their site; this is very courageous of them - because her piece, titled "The Kremlin Actively Recruits Western Experts to Improve Russia's Image," is very very critical of this whole endeavor and of the people who chose to participate in it.

Albats, a highly esteemed Russian journalist and member of the Center for Public Integrity's International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, tackles an issue that none of those who attended the conference and the meeting with Putin have so far chosen to focus much on: the money issue.

Money was not spared on improving Russia's image abroad.

"They paid for roundtrip business-class airfare, though we could only take Aeroflot. If I had wanted to take my wife they would have paid for her, too," said David Johnson of the Center for Defense Information, a bit perplexed by the Russians' generosity. Johnson puts together a summary of news and views about Russia from publications worldwide, sends it out daily by email to about 5,000 subscribers and also places the information on his Web site. Journalists and political scientists consider it an honor to be featured in his summaries: Johnson's reputation is impeccable.

Thus, the operation aimed at influencing Western public opinion about Russia was made according to a well-established Russian public relations rule: he who pays the piper calls the tune. According to a former deputy who spoke on condition of anonymity, there is a little known line item in the federal budget that provides for financing events that enhance Russia's image.

In total, 42 guests were invited to the conference. Airfare was paid for; accommodations were provided at the Metropol, where the cheapest room costs $300 a night. All other expenses, including travel to and accommodations in Veliky Novgorod, were covered by RIA Novosti; in other words, the state picked up the tab.

Several journalists were also in attendance. I was sure that they had covered their expenses themselves: the ethics codes of many Western publications specifically bar journalists from allowing information sources to even pay for lunch, let alone a $2,500 first-class airline ticket. As it turns out, I was wrong.

"It isn't corruption," Jonathan Steele said, responding to my question about who covered his costs at the conference. [...]

Steele said that corruption happens when substantial royalties are paid, but that covering journalists' expenses is quite common among English newspapers. "Sometimes we indicate at the end of an article that expenses associated with its preparation were paid for [by someone besides the paper]," he said.

None of Steele's reports from Moscow, however, refers to the Russian government covering his expenses. True, he mentions in one report that the Russian president held a meeting with Western scholars and journalists who were attending a "special conference." But he does not disclose the fact that the aim of the conference was to enhance Russia's image abroad.

Comments provided to Albats by Mary Dejevsky of The Independent are quite telling, too:

Mary Dejevsky of the Independent, a British daily, had her own reasons for accepting the conference organizers' invitation and payment of her expenses. In a telephone interview, she said her paper weighs the importance of gaining access to representatives of foreign governments, and depending on that, such an invitation is accepted or rejected.

She said that if she had decided not to attend the conference, she would not have been able to tell her readers about this meeting with President Putin. [...]

"But what kept your paper from covering the expenses associated with getting such important information for your readers," I asked. Dejevsky said that while some organizations such as the BBC operated that way, her paper had a different policy. If she had refused to accept the offer, she might not have obtained access to such high-ranking Russian officials, she said.

However, there was indeed a non-free way to get access to Putin and other high-ranking Russian officials, according to Albats:

American television journalist Eileen O'Connor, who for many years headed CNN's Moscow bureau, also attended the conference, also was present at the meetings with Putin and Ivanov, and also was offered to have her expenses taken care of by conference organizers. O'connor turned down the offer. She informed the organizers that she would pay for both her flight and hotel expenses. O'Connor had come to Russia not as a news correspondent, but president of the nonprofit International Center for Journalists.

Obviously, Albats did not attend the conference and the meeting with Putin; allowing her in might have proved as detrimental to Russia's image as inviting Anna Politkovskaya, an outspoken Russian journalist who, allegedly, was poisoned on her way to Beslan, and thus prevented from covering the tragedy. According to Dejevsky, though, the real reason for leaving many of the local journalists out had to do with - ironically - money:

Responding to another question, Dejevsky explained that the reason Russian journalists were not invited to attend the meetings with Putin and Ivanov was due to the fact that Russian politicians "trust western reports more than they do the Russian press." She told me that the Russian press was extremely corrupt, was always writing stories for money, and that such practices could not be found anywhere among Western newspapers.

After I read Albats' piece, I was very curious about Dejevsky's post-Sept. 6 reports. But here the money issue struck again: I was too late to catch her stories while they were still available for free reading online. I looked for them on The Independent site, about a week ago, and the cheapest option for me was to pay "£1 for 24 hours' access to this article" - but I don't have a credit card and, even if I did, it'd still be such a waste, for why on earth would I need 24 hours to read a newspaper story? (The Valdai Discussion Club site has reprinted Dejevsky's stories not from The Independent but from The Belfast Telegraph - and this paper's options are significantly cheaper: they are asking just "50p for 24 hours' access to this article.")

In any case, I'm grateful to the Valdai Discussion Club people for giving me a chance to read two of Dejevsky's stories free of charge. One important thing that I've found out is that Putin didn't say he was prepared to violate the Russian Constitution in order to grant "maximum autonomy" to Chechnya, as Fiona Hill of the Brookings Institution wanted everyone to believe.

Here's what Dejevsky wrote on the issue in her first piece (Sept. 7):

In an unexpected change of tone, however, Vladimir Putin also held out the prospect of a more conciliatory line towards Chechnya, praising Chechen traditions and suggesting there was a possibility of broad-based parliamentary elections there. [...]

Seeming to extend an olive branch to a much broader swath of Chechen opinion than hitherto, Mr Putin said: "We will continue our dialogue with civil society. This will include holding parliamentary elections, trying to get as many people as possible involved, with as many views and policies as possible.' One of the big criticisms of Russia's policy in Chechnya is that it has held presidential elections from which the more popular opposition figures have been excluded, but delayed parliamentary elections.

Mr Putin gave a clear indication that he was open to the holding of parliamentary elections in Chechnya - although he did not give a date - in the hope of drawing many more people into the political process. He also said that the intention was to "strengthen law enforcement by staffing the police and other bodies in Chechnya with Chechens'.

The two moves together would amount to the continuation, even acceleration, of the policy of "Chechenisation', which some believed would be reversed after the spate of recent attacks in Russia: the downing of two planes, a bomb near a Moscow underground station, and, last week, the siege of School Number One in Beslan that cost more than 300 lives. [...]

In a little-noticed move two weeks before the attacks, the Russian government had decreed that Chechnya should be able to keep revenue from its oil, rather than remit the proceeds to Russia as currently happens. This was a major change in policy and one that irritated other regions that do not enjoy a similar right.

Mr Putin insisted, however, that Russia would retain troops in Chechnya. Their withdrawal is one of the separatists' main objectives. Russia had as much right to keep troops in the region as the US has to station its troops "in California or Texas', he said.

While I find this oil revenue initiative interesting and will definitely look for more information on it, I still don't understand how all this endless talk about parliamentary election in Chechnya could be considered "an unexpected change of tone." And does Putin only "seem" to "extend an olive branch" - and if yes, how could it possibly be considered "a clear indication that he was open to the holding of parliamentary elections in Chechnya"? (Though I have to admit that, no matter how subjective Dejevsky's conclusions are, they are almost timid compared to the assertions Fiona Hill has made in her New York Times op-ed.)

In her Sept. 8 piece - "Evening of Surprises With a Hospitable President" - Dejevsky writes in great detail about the idyllic atmosphere of Putin's Novo-Ogaryovo residence and his great personal charm. All of this is, of course, sickeningly irrelevant to what had happened in Beslan just five days earlier. Actually, it's so sickening that I won't quote any of it here - I've provided the link to this piece at the beginning of this entry.

As for the confirmation of Fiona Hill's "maximum autonomy" comment - I haven't found it here, either. As in other sources, all Putin is quoted saying is this:

On inter-ethnic disputes and criticism of Russia's Chechnya policy he retorted: "No one can accuse us of not being flexible in our dealings with the Chechen people. In 1995, we granted them de facto autonomy, but what happened was complete chaos, unbelievable violence. [...]"

The Independent ran another post-Sept. 6 piece, which hasn't yet been posted on the Valdai Discussion Club site but is still somehow available free of charge: "Eyeball to Eyeball With Vladimir Putin" by John Kampfner, political editor of the New Statesman. In it, Kampfner treats Putin the way all presidents deserve to be treated: as politicians. This is the attitude that won't make Kampfner blush in the future:

My extraordinary encounter with the Russian President on Monday night, as part of a group of mainly foreign academics, provided an insight, however fleeting, into the psychology of a president in whose name systematic human rights abuses have been committed.

The question that needs answering is not whether Putin is an evil man wilfully destroying Chechnya. It is not whether the depraved mass murder of children in Beslan was the result of his policies towards the Caucasus or simply a dreadful extension of global terror. The only useful question is, what do we do about it? [...]

So can anyone influence Putin, and, if so, how? The impression I came away with after listening to him for so long was ... possibly. The negatives were abundantly clear. He will not withdraw Russian troops. He will not negotiate with Chechen political leaders, whom he calls "child-killers". He is possessed of a Soviet-era conspiracy that certain forces in the West are helping the Chechens in order to destabilise Russia. He seems unapologetic in his persecution of journalists who seek to "undermine" the stability of the state.

Each statement was icily but eloquently delivered. [...]

This all sounds good. It's funny, though that the very next thing Kampfner chooses to allude to is, possibly, Yevgenia Albats' piece:

Some Russian journalists wrote afterwards that we Westerners had been picked out because we might be more gullible. Anyone who looks back at the reporting of Mary Dejevsky, Jonathan Steele or myself during Soviet times might think again. One does not have to enjoy being with Putin or agree with him to try to understand him.

This is a good point, gracefully delivered, and, moreover, it doesn't contradict what Albats wrote about Mary Dejevsky: "...I cannot help mentioning that in contrast to Mary Dejevsky the reporter, Mary Dejevsky the columnist does not at all hide her sympathy for Russia's current leadership."

Kampfner's conclusions appear quite solid at first:

Putin will eventually be forced to negotiate with the Chechens - all wars end that way. But it would be impossible for him to proceed soon, even if he wanted to, after such an attack. No world leader would do that. This is a man who is evidently not exercised by questions of democracy or human rights. What seems to matter to him personally, and the issue on which he has twice based his electoral appeal, is security. Putin has to be convinced that Russia's stability is jeopardised, not enhanced, by continuing the war. He has to be convinced that the West has no interest in seeing Russia weakened. He has to be shown that international mediation - most likely through the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe - will not be a humiliation. In a sense we may have to go back to the 1980s, to the era of detente and constructive engagement. Unlike that period, however, Russia is much more of a danger to itself and to its outlying regions than it is to us. We need to be wary but ready to become involved, rather than shouting from the rooftops.

Nothing will be gained from indulging Putin or denouncing him. The only possible chance we have in this desperate situation will come from steady, measured but incessant pressure.

Kampfner is not "shouting from the rooftops" - but, unfortunately, he seems to be viewing the situation in Russia from as high up as a rooftop. If Beslan, and the Nord-Ost theater siege, and the numerous deadly explosions haven't been convincing enough, what else has to happen that would force Putin to reconsider some of his policies? On the other hand, there's a very sobering element in Kampfner's argument: if Russia is more dangerous to itself than it is to the West (which it sure is), then why does the West have to bother too much about getting involved? Even if we take the scary "domino effect" factor into account, isn't it more reasonable for the Russian citizens (including the Chechens and their neighbors) to try to get more involved first?

Wednesday, September 22, 2004

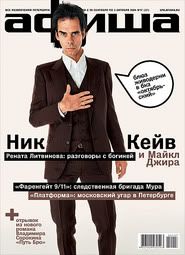

Nick Cave played here in St. Pete yesterday.

I'd have preferred to see him at a venue more intimate than the Oktyabrsky Concert Hall, a humongous, Soviet-ly gray and ugly place - but I'm not complaining. Mishah and I sat in the left corner of the last row of the balcony, almost on the roof - you can't get further than that - and again, I'm not complaining. I'm very happy I was there yesterday.

He played one of my favorite songs, the one that was originally recorded with PJ Harvey - "Henry Lee." There's always something in this song that I don't understand. Eight years ago, you should've seen me, a totally drunk 22-year-old, chasing a few Americans at an Easter party in Kyiv, trying to get them to explain a line or two that I couldn't quite make out. These Americans were, at the time, almost done drafting the Ukrainian constitution, no less. Now, both the lyrics and the constitution are available online. And yesterday, Nick Cave strayed from the original "Henry Lee" and shouted out something that began with "AND YOU RUSSIAN FUCKERS" - and I couldn't make out the rest of it. I suspect it was something about Chechnya - or maybe not. I hope eventually I'll find someone who heard it better than I did. (P.S. - 09/24 - Well, my friends who've also been to the concert told me it wasn't about Chechnya, not directly, at least - supposedly, he told the Russian fuckers to draw some kind of a lesson from Henry Lee's experience.)

Tuesday, September 21, 2004

Within hours after I posted the entry about the current mess in Iraq and in Chechnya, and the past mess in Lebanon, I ran into this 20-year-old story about a 1984 attack on the U.S. embassy in Beirut (The Guardian, "Suicide Bombers Kill 23 in Attack on Embassy," by David Hirst, Sept. 21, 1984).

A strange coincidence, but I'm a lot more amazed at how familiar this 20-year-old account is:

The impression that I was reading something written today - some kind of a template, perhaps, in which one only needs to substitute the names and the figures - didn't leave me until the very last paragraph: it was then that I realized I still hadn't stumbled on the mention of al-Qaeda or the ubiquitous shorthand for all that's evil, "international terrorism." Instead, there was this:

I decided to go back to Thomas Friedman's book and see if there was anything on David Hirst in it, the journalist who wrote this 20-year-old story. I was happy to find a rather amusing episode featuring him - I was happy because I feared he might have been killed at some point in his career, covering the war in Lebanon. I later checked Hirst's name on the web and found he was still out there, commenting extensively on the current situation in Iraq and the rest of the Middle East.

Honestly, I don't have enough zeal in me to study his current work at all - after reading this 20-year-old Beirut piece, all this fighting, in the Middle East or elsewhere, seems neverending, unstoppable, pointless and, to use a pun, done to death. There probably exist the good guys and the bad guys - only twenty years later the difference between them blurs almost completely, and the only thing that continues to shock is how many lives have been wasted in vain.

So here's the amusing episode from Thomas Friedman's "From Beirut to Jerusalem":

A strange coincidence, but I'm a lot more amazed at how familiar this 20-year-old account is:

A suicide car-bomber struck at the US embassy in Beirut yesterday for the second time in 18 months, killing at least 23 people, including two US diplomats, and wounding scores of others. The attack, claimed by the Islamic Jihad organisation as part of a campaign to drive every American from Lebanese soil, wrecked the annexe to the embassy, which recently opened in a quiet suburb of Christian East Beirut. [...]

One report said that the guards killed the driver but, if so, he nonetheless managed to cover the 30 yards or so between the barrier and the building [...]

The vehicle - a station wagon with Dutch diplomatic plates - exploded a yard or so from it, gouging a crater two yards deep and six wide. Although the building did not collapse - as happened last time - its ground floor was devastated and its upper floors badly damaged. Cars in the embassy compound were incinerated, wreckage and human remains scattered 200 yards, and windows were broken up to a kilometre away.

Most of the dead and wounded were Lebanese. [...]

In a telephone message to Agence France Presse a caller identifying himself as a spokesman for the Islamic Jihad said: 'In the name of God Almighty, the Islamic Jihad organisation announces that it is responsible for blowing up a car packed with explosives which was driven by one of our suicide commandos into a housing compound for the employees of the US embassy in Beirut .

'This operation comes to prove that we will carry out our promise not to allow a single American to remain on Lebanese soil. When we say Lebanese soil we mean every inch of Lebanese territory.

'We also warn our Lebanese brothers and citizens to stay away from US installations and gathering points, especially the embassy. We are the strongest.'

The Islamic Jihad, none of whose members has ever made a public appearance, is generally assumed to be Shi'ite fundamentalist sect, with Iranian and possible Syrian connections.

It has carried out several suicide missions. It claimed responsibility for killing 63 people, 17 of them Americans, in the explosion which destroyed the US embassy in its original, seafront location in West Beirut in April last year, and for the slaughter of 242 US Marines in their quarters next to Beirut airport in November. [...]

The impression that I was reading something written today - some kind of a template, perhaps, in which one only needs to substitute the names and the figures - didn't leave me until the very last paragraph: it was then that I realized I still hadn't stumbled on the mention of al-Qaeda or the ubiquitous shorthand for all that's evil, "international terrorism." Instead, there was this:

Yesterday's exploit illustrates again that there is no foolproof precaution against the ultimate self-sacrifice of the car-bomb.

I decided to go back to Thomas Friedman's book and see if there was anything on David Hirst in it, the journalist who wrote this 20-year-old story. I was happy to find a rather amusing episode featuring him - I was happy because I feared he might have been killed at some point in his career, covering the war in Lebanon. I later checked Hirst's name on the web and found he was still out there, commenting extensively on the current situation in Iraq and the rest of the Middle East.

Honestly, I don't have enough zeal in me to study his current work at all - after reading this 20-year-old Beirut piece, all this fighting, in the Middle East or elsewhere, seems neverending, unstoppable, pointless and, to use a pun, done to death. There probably exist the good guys and the bad guys - only twenty years later the difference between them blurs almost completely, and the only thing that continues to shock is how many lives have been wasted in vain.

So here's the amusing episode from Thomas Friedman's "From Beirut to Jerusalem":

Unfortunately, when reporters were left to probe to the limits of their own bravery, it meant inevitably that some went too far. During Israel's 1978 incursion into south Lebanon, up to the Litani River, David Hirst of The Manchester Guardian, Ned Temko of The Christian Science Monitor, and Doug Roberts of the Voice of America rode down from Beirut to observe the fighting. They were told by Palestinian guerrillas in Sidon that the PLO had just driven the Israeli army out of the nearby village of Hadatha. The three reporters decided to check out the story and found that actually the Israeli army had driven the Palestinians out of Hadatha and then vacated it. When Israeli gunners saw the three journalists drive in, they thought they were returning guerrillas and fired rounds at them on and off for eight hours. The next day the three "surrendered" to a unit of Israeli soldiers sitting on a nearby hilltop and were taken back to Israel for their own safety. As soon as they crossed the border, an Israel Radio reporter walked up to David Hirst and asked him how it felt to be rescued by the Israeli army.

"After they stopped shooting at us," answered David, "it was fine."

Monday, September 20, 2004

A story in The New York Times from three days ago - "For Some Beslan Families, Hope Itself Dies Agonizingly" (by SETH MYDANS, published Sept. 17, 2004) - too horrible, too painful to read:

This photo (by James Hill for The New York Times) accompanies the story:

Caption: A mother and her child Thursday examined the pictures of victims of the Beslan school siege not yet identified or found. A picture was removed after one victim was found, though whether dead or alive is not known.

In today's story, "In Ethnic Tinderbox, Fear of Revenge for School Killings," Seth Mydans reports from an Ingush-populated town of Kartsa that "[b]oth here and in Beslan, people are talking about Oct. 13, the end of a 40-day mourning period, when the traditional moment comes to contemplate revenge."

This is not a nation whose government responds to the outcries of the bereaved, and they have been left on their own like the survivors and families in past disasters in Russia.

They plead with one official after another for help; they search hospitals in distant cities; they pick through bits and pieces of bone and flesh and teeth that have been set aside at the morgue like trays of party favors.

This photo (by James Hill for The New York Times) accompanies the story:

Caption: A mother and her child Thursday examined the pictures of victims of the Beslan school siege not yet identified or found. A picture was removed after one victim was found, though whether dead or alive is not known.

In today's story, "In Ethnic Tinderbox, Fear of Revenge for School Killings," Seth Mydans reports from an Ingush-populated town of Kartsa that "[b]oth here and in Beslan, people are talking about Oct. 13, the end of a 40-day mourning period, when the traditional moment comes to contemplate revenge."

AFTER BESLAN: NOTES ON THE COVERAGE (5)

Here's another passage from Jonathan Steele's Sept. 8 piece on the meeting with Putin two days earlier:

And here's one of those comments, which I don't find too enthralling, candid or surprising - though perhaps you have to be there in one room with Putin to get so charmed. Reading it from afar, I feel nothing but repulsion:

Putin didn't say Bush had actually managed to normalise the situation in Iraq - that could pass as candid, I guess, if it didn't require all that reading between the lines. And if what's happening in Iraq now - the hostages, explosions and all - is close to normal, then Chechnya must be like Sweden, close to perfect.

It all suddenly reminded me of one of my favorite passages from Thomas Friedman's book, "From Beirut to Jerusalem." The passage - stuck in the middle of the chapter called "The End of Something" - is about Nabil Tabbara, a Beiruti architect and professor of architecture:

This last quote never fails to make me cry and laugh at the same time.

In the first chapter (titled "Would You Like to Eat Now or Wait for the Cease-Fire?"), Friedman writes this about Beirut:

He quotes from Hobbes, too, in that chapter:

Some of it is probably an exaggeration when applied to contemporary Chechnya, but as a metaphor it's as good as any: comparing Chechnya's capital Grozny today to what Beirut was some twenty years ago is as evocative as calling Chechnya "a Hobbesian state" - something that David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker, promptly does in his most recent commentary ("Prisoners of the Caucasus," issue of Sept. 20, 2004; posted on the web on Sept. 13, 2004):

Although Remnick does refer in his piece to the Sept. 6 meeting with Putin, he, unlike a few others, doesn't appear charmed or misled in any way - maybe because he didn't attend the meeting and thus has managed to keep his common sense intact:

Here's another passage from Jonathan Steele's Sept. 8 piece on the meeting with Putin two days earlier:

If Vladimir Putin was feeling the pressure after possibly his worst week in office, it didn't show. During a rare and wide-ranging interview at his country house outside Moscow, the president enthralled a group of handpicked journalists and academics, giving candid comments that offered surprising insights.

And here's one of those comments, which I don't find too enthralling, candid or surprising - though perhaps you have to be there in one room with Putin to get so charmed. Reading it from afar, I feel nothing but repulsion:

Although Russia would not send troops or join in training the Iraqi army and police, [Putin] said: "We want to do everything to normalise things there. I think Bush has done a lot to normalise the situation. Given all the complexities, he's been able to achieve his aims. We will refrain from anything which might be met negatively by the Iraqi people."

Putin didn't say Bush had actually managed to normalise the situation in Iraq - that could pass as candid, I guess, if it didn't require all that reading between the lines. And if what's happening in Iraq now - the hostages, explosions and all - is close to normal, then Chechnya must be like Sweden, close to perfect.

It all suddenly reminded me of one of my favorite passages from Thomas Friedman's book, "From Beirut to Jerusalem." The passage - stuck in the middle of the chapter called "The End of Something" - is about Nabil Tabbara, a Beiruti architect and professor of architecture:

Like many of his generation, Tabbara [...] grew up being taken by his father on trips through the Beirut city center. The smell of the bazaar there, its spices and breads, its colors and sounds, and, most of all, the warmth of people mixing together, would always be part of his identity and his sense of Beirut as home. At the height of the civil war in 1976, it appeared that the graceful stone archways and marketplaces of the old city center were going to be destroyed forever. To keep a personal archive for himself of the Beirut he cherished, Tabbara took a leave from his architectural job and decided in the middle of the civil war that he would try to sketch and photograph what remained of the city center before it vanished.

"I didn't know what would be left of the old Beirut," Tabbara explained when I asked him what motivated this personal adventure, "and I always remembered the people of Warsaw who broke into their municipal archives after the Nazis invaded and hid all the plans and drawings of the Warsaw city center, which they used to rebuild it later."

Armed only with his Nikon camera, pencil, and sketchpads, Tabbara spent a month obtaining passes from all the different Muslim and Christian militias fighting along the Green Line, in order to freely enter the battle zone. Then he headed off to capture the last remnants of his youth.

"I would go down to the Phoenicia Hotel every morning, park my car, and then walk to the Green Line," he recalled. "At first the gunmen would say, 'Look at this fool sitting on the rubble sketching with the rockets and bullets going by.' They thought I was absolutely crazy. But after a while they really got into what I was doing. Some days they would lay down a barrage of machine-gun fire to cover me, so I could run across the dangerous street, or they would break into a building so I could get a particular view from the roof."

This last quote never fails to make me cry and laugh at the same time.

In the first chapter (titled "Would You Like to Eat Now or Wait for the Cease-Fire?"), Friedman writes this about Beirut:

I don't know if Beirut is a perfect Hobbesian state of nature, but it is probably the closest thing to it that exists in the world today.

He quotes from Hobbes, too, in that chapter:

In his classic work Leviathan, the seventeenth-century English political philosopher Thomas Hobbes described what he called "the state of nature" that would exist if government and society completely broke down and the law of the jungle reigned. In such a condition, wrote Hobbes, "where every man is enemy to every man ... there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodities building; no instruments of moving, and removingm such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short."

Some of it is probably an exaggeration when applied to contemporary Chechnya, but as a metaphor it's as good as any: comparing Chechnya's capital Grozny today to what Beirut was some twenty years ago is as evocative as calling Chechnya "a Hobbesian state" - something that David Remnick, editor of The New Yorker, promptly does in his most recent commentary ("Prisoners of the Caucasus," issue of Sept. 20, 2004; posted on the web on Sept. 13, 2004):

Chechnya today is as close to a Hobbesian state as exists on earth. Grozny is a moonscape of gas fires, open sewers, and bombed-out buildings. There is almost no legitimate economy: at least seventy-five per cent of the Chechen workforce is unemployed. Criminal gangs dominate the social order. Politicians are assassinated; journalists and aid workers are abducted, even executed. The Russian Army troops who remain are corrupt, lawless, given to raping, kidnapping, and executing civilians. Whatever funds Moscow sends for rebuilding invariably end up stolen.

Although Remnick does refer in his piece to the Sept. 6 meeting with Putin, he, unlike a few others, doesn't appear charmed or misled in any way - maybe because he didn't attend the meeting and thus has managed to keep his common sense intact:

The note Putin struck most distinctly at the meeting with reporters and scholars was one of paranoia, fear that outside forces—the enemies he knew as a K.G.B. officer--were somehow undermining him. Those who mean to “tear off a big chunk of our country,” he said, are being backed by those who “think that Russia, as one of the greatest nuclear powers of the world, is still a threat, and this threat has to be eliminated.”

And so the Russian people, who live in dread of further violence, find themselves at the mercy of well-trained terrorists in the south and a paranoid President in the Kremlin who refuses the burdens of democratic accountability and the need to reshape a policy that is good for little but more bloodshed. [...]

Saturday, September 18, 2004

AFTER BESLAN: NOTES ON THE COVERAGE (4)

Before I move on to the more serious stuff, here's a little something that made me laugh while I was researching for the piece below:

- It looks like Democracy Now!, a daily radio and TV news program, employs a transcriber who knows very little about Chechnya (which is not too surprising - nor is it too bad in any way). He/she wrote this in the "rush transcript" of one of Amy Goodman's programs:

Of course, Mr. Peterson said "Ingush" - not "English"... Though, if you think about it, they do sound alike...

- On the same show, the following exchange took place between Amy Goodman and her next guest, Mary Dejevsky of The Independent, who had attended the meeting with Putin on Sept. 6 (the serious part of this entry is more or less about that meeting):

I love the ambiguity of it.

On to the more serious stuff...

***

Fiona Hill, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who was quoted in The Christian Science Monitor's Sept. 10 story saying Putin had "offered [Chechnya] 'maximum autonomy, even to the point of violating the Russian constitution,'" had her own op-ed piece published in The New York Times on the same day:

In the article, titled "Stop Blaming Putin and Start Helping Him," Ms. Hill stated that "[c]learly, he was sending a message that he needs the United States and Europe to pay careful attention as he responds to the massacre." She also repeated what she had told The Christian Science Monitor:

Shortly after Ms. Hill had made her observations public, Putin ordered major electoral changes, which were criticized by some and praised by others. These changes appear to be the opposite of what Ms. Hill claimed he had been "prepared" to do.

I've examined a few other accounts of Putin's Sept. 6 meeting with Western analysts and journalists, to see if any carried confirmation of Ms. Hill's optimistic claims. So far, I haven't succeeded.

David Johnson posted his notes on Johnson's Russia List (JRL, a superb resource on Russia, updated regularly by Mr. Johnson). He wrote that the meeting "was planned some time before the recent terror events in Russia and was a direct follow-on to the Valdai Discussion Club conference held September 3-4 in Veliky Novgorod. The conference was organized primarily by RIA Novosti and the [Russian] Council on Foreign and Defense Policy." Mr. Johnson's feeling is that "Putin was not thinking of the event as a press conference. It was more of a thoughtful discussion with long-time Russia-watchers, not a news-generating event." Hence, the sketchiness of his notes and this warning: "I would suggest that nothing here is worthy of further quotation. It's more useful in giving an impression of what was said than as an accurate record of details. ACTUALLY: DON'T QUOTE FROM THIS!"

I'll quote just one tiny thing: the following summary of Putin's words - "The Chechen constitution provides an enormous amount of autonomy." - refers to the constitution adopted as the result of a March 2003 referendum in Chechnya, not to anything intended in the near future.

The Guardian's Jonathan Steele also did not write anything that would confirm Ms. Hill's claim - neither in his partial notes from the meeting posted on JRL, nor in his Guardian pieces of Sept. 7 and Sept. 8.

In his Sept. 7 story, "Angry Putin Rejects Public Beslan Inquiry," Mr. Steele reported Putin's interest in finding a political solution to the situation in Chechnya:

But holding parliamentary elections in Chechnya is in complete accordance with the constitutions of both Chechnya and the Russian Federation. Also, there is nothing new/newsworthy in the fact that Putin says the election is going to take place - he has been reported to imply it in 2003, prior to the referendum ("'A constitution accepted by its people would become a basis for a political settlement in Chechnya, allowing them choose truly democratic authorities that would rely on popular trust,' Putin said, stressing that the republic would not be allowed to secede."), and he also mentioned it as recently as August 16, 2004 ("Russian President Vladimir Putin has said there is a need to hold parliamentary elections in Chechnya as soon as possible after the presidential elections.").

(On a different note, "angry Putin" calmed down a bit and, four days later, announced that a parliamentary inquiry would be conducted by the Federation Council, the upper house of the Parliament, whose members are not elected but appointed by the 89 federal subjects. But if you think there's much discussion here on where this inquiry might possibly lead and what horrible truths it would likely uncover - no, there's almost none, everyone's busy talking about Putin's undemocratic reorganization plans.)

Mr. Steele's Sept. 8 article, "Candid Putin Offers Praise and Blame," cast more doubt on the accuracy of Ms. Hill's remark: Putin, angry yesterday but candid today, "made it clear beyond doubt that he had not changed his policy on Chechnya after Beslan."

On JRL, in a note that precedes the transctipt of Putin's answers, Mr. Steele pointed out two things that made me suspect that neither Ms. Hill nor Putin were actually lying. Mr. Steele wrote that he "was the only person in the group who was taping the meeting" and, moreover, he "had only budgeted for a 90-minute meeting, and did not have enough tape for the entire encounter" (halfway through the transcript, this note was inserted: "Tape was changed over to the other side here, and a few sentences were lost"). Further, Mr. Steele wrote that the interpreter's "English was not perfect" - which is exactly what I was thinking a few days before: that they had a lousy translator!

So it is possible that Ms. Hill could have assumed that she heard something that hadn't actually been said - and I don't blame her for that. She didn't have a chance to correct her mistake because Mr. Steele was the only one with a tape recorder there - and since he ran out of tape, the part of Putin's speech that so confused Ms. Hill might have been missing.

But then she reported it all, and based much of her argument on the assumption that Putin was prepared to violate the Russian Constitution in order to give Chechnya broader autonomy - and The New York Times published Ms. Hill's op-ed piece without checking the facts first.

I wonder if they have posted a correction yet. Maybe they will. I hope someone will let me know if I miss it.

Before I move on to the more serious stuff, here's a little something that made me laugh while I was researching for the piece below:

- It looks like Democracy Now!, a daily radio and TV news program, employs a transcriber who knows very little about Chechnya (which is not too surprising - nor is it too bad in any way). He/she wrote this in the "rush transcript" of one of Amy Goodman's programs:

AMY GOODMAN: Has it been discovered yet exactly who the people are who did this?

SCOTT PETERSON [The Christian Science Monitor correspondent who wrote the piece I'm referring to at the very beginning of the serious part of this entry as well as in one of the previous entries; speaking on the phone from Beslan]: No. The authorities, even if they know, have not really been that specific yet. So, we're waiting to hear about that. It's not clear that we will ever know because Russia is not really known for its openness on this kind of issue. But certainly we have - I mean from the hostage survivors, I mean, they indicate that people - Chechnyan and English people took part. Hostages that I spoke to said that they didn't see any foreigners; but anyway, I think that the truth really remains to be seen.

Of course, Mr. Peterson said "Ingush" - not "English"... Though, if you think about it, they do sound alike...

- On the same show, the following exchange took place between Amy Goodman and her next guest, Mary Dejevsky of The Independent, who had attended the meeting with Putin on Sept. 6 (the serious part of this entry is more or less about that meeting):

AMY GOODMAN: We're talking with Mary Dejevsky who was with President Putin last night. Can you talk about the scene where he slammed on the table?

MARY DEJEVSKY: I'm sorry?

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the scene where President Putin last night, where he slammed on the table, expressing anger?

MARY DEJEVSKY: Yes. I wouldn't say he slammed on it. He clenched his fists. He didn't pound them on the table. He was much more controlled than that [...]

I love the ambiguity of it.

On to the more serious stuff...

***

Fiona Hill, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who was quoted in The Christian Science Monitor's Sept. 10 story saying Putin had "offered [Chechnya] 'maximum autonomy, even to the point of violating the Russian constitution,'" had her own op-ed piece published in The New York Times on the same day:

On Monday, against the backdrop of the terrorist attack in Beslan, President Vladimir Putin of Russia held a remarkable four-hour discussion with a small group of American and Western European journalists and analysts at his official residence at Novo-Ogaryovo, outside Moscow. The meeting had been scheduled as part of a two-day conference on Russian-Western relations, but given the unfolding horrors at School No. 1, we were certain it would be canceled. Instead, President Putin turned it into a very personal exercise in public diplomacy.

In the article, titled "Stop Blaming Putin and Start Helping Him," Ms. Hill stated that "[c]learly, he was sending a message that he needs the United States and Europe to pay careful attention as he responds to the massacre." She also repeated what she had told The Christian Science Monitor:

President Putin told us that he was prepared to offer a great deal of autonomy to Chechnya, even to the point of "violating the Russian Constitution." This is something that he has resisted for some time, despite heavy pressure from some of his advisers and international opinion.

Shortly after Ms. Hill had made her observations public, Putin ordered major electoral changes, which were criticized by some and praised by others. These changes appear to be the opposite of what Ms. Hill claimed he had been "prepared" to do.

I've examined a few other accounts of Putin's Sept. 6 meeting with Western analysts and journalists, to see if any carried confirmation of Ms. Hill's optimistic claims. So far, I haven't succeeded.

David Johnson posted his notes on Johnson's Russia List (JRL, a superb resource on Russia, updated regularly by Mr. Johnson). He wrote that the meeting "was planned some time before the recent terror events in Russia and was a direct follow-on to the Valdai Discussion Club conference held September 3-4 in Veliky Novgorod. The conference was organized primarily by RIA Novosti and the [Russian] Council on Foreign and Defense Policy." Mr. Johnson's feeling is that "Putin was not thinking of the event as a press conference. It was more of a thoughtful discussion with long-time Russia-watchers, not a news-generating event." Hence, the sketchiness of his notes and this warning: "I would suggest that nothing here is worthy of further quotation. It's more useful in giving an impression of what was said than as an accurate record of details. ACTUALLY: DON'T QUOTE FROM THIS!"

I'll quote just one tiny thing: the following summary of Putin's words - "The Chechen constitution provides an enormous amount of autonomy." - refers to the constitution adopted as the result of a March 2003 referendum in Chechnya, not to anything intended in the near future.

The Guardian's Jonathan Steele also did not write anything that would confirm Ms. Hill's claim - neither in his partial notes from the meeting posted on JRL, nor in his Guardian pieces of Sept. 7 and Sept. 8.

In his Sept. 7 story, "Angry Putin Rejects Public Beslan Inquiry," Mr. Steele reported Putin's interest in finding a political solution to the situation in Chechnya:

[Russia is] going to hold elections to a Chechen parliament there shortly "and we will try to attract as many people as possible with different views to take part".

"We will strengthen law enforcement by staffing the police with Chechens, and gradually withdraw our troops to barracks, and leave as small a contingent as we feel necessary, just like the US does in California and Texas," [Putin] said.

He could not agree that a war was still going on there five years after he first sent in troops. "It is a smouldering conflict. There have been attacks but not like the big operations of 1999," he said.

But holding parliamentary elections in Chechnya is in complete accordance with the constitutions of both Chechnya and the Russian Federation. Also, there is nothing new/newsworthy in the fact that Putin says the election is going to take place - he has been reported to imply it in 2003, prior to the referendum ("'A constitution accepted by its people would become a basis for a political settlement in Chechnya, allowing them choose truly democratic authorities that would rely on popular trust,' Putin said, stressing that the republic would not be allowed to secede."), and he also mentioned it as recently as August 16, 2004 ("Russian President Vladimir Putin has said there is a need to hold parliamentary elections in Chechnya as soon as possible after the presidential elections.").

(On a different note, "angry Putin" calmed down a bit and, four days later, announced that a parliamentary inquiry would be conducted by the Federation Council, the upper house of the Parliament, whose members are not elected but appointed by the 89 federal subjects. But if you think there's much discussion here on where this inquiry might possibly lead and what horrible truths it would likely uncover - no, there's almost none, everyone's busy talking about Putin's undemocratic reorganization plans.)

Mr. Steele's Sept. 8 article, "Candid Putin Offers Praise and Blame," cast more doubt on the accuracy of Ms. Hill's remark: Putin, angry yesterday but candid today, "made it clear beyond doubt that he had not changed his policy on Chechnya after Beslan."

On JRL, in a note that precedes the transctipt of Putin's answers, Mr. Steele pointed out two things that made me suspect that neither Ms. Hill nor Putin were actually lying. Mr. Steele wrote that he "was the only person in the group who was taping the meeting" and, moreover, he "had only budgeted for a 90-minute meeting, and did not have enough tape for the entire encounter" (halfway through the transcript, this note was inserted: "Tape was changed over to the other side here, and a few sentences were lost"). Further, Mr. Steele wrote that the interpreter's "English was not perfect" - which is exactly what I was thinking a few days before: that they had a lousy translator!

So it is possible that Ms. Hill could have assumed that she heard something that hadn't actually been said - and I don't blame her for that. She didn't have a chance to correct her mistake because Mr. Steele was the only one with a tape recorder there - and since he ran out of tape, the part of Putin's speech that so confused Ms. Hill might have been missing.

But then she reported it all, and based much of her argument on the assumption that Putin was prepared to violate the Russian Constitution in order to give Chechnya broader autonomy - and The New York Times published Ms. Hill's op-ed piece without checking the facts first.

I wonder if they have posted a correction yet. Maybe they will. I hope someone will let me know if I miss it.

Thursday, September 16, 2004

AFTER BESLAN: NOTES ON THE COVERAGE (3)

On Friday, Sept. 10, 2004, The Christian Science Monitor ran a story that wasn't just soft on President Putin and the FSB - it was groundlessly optimistic about the steps the Russian leadership would be likely to take after the tragedies of the past two weeks ("Russia Shapes Plan of Attack" by SCOTT PETERSON):

This forecast turned out to be naive, even silly: three days after this piece appeared, on Monday, Sept. 13, Putin ordered a drastic political overhaul, which, many say, is unconstitutional, would do little to prevent further terrorist attacks and would make this country resemble the Soviet Union more than ever before in the past decade or so. Even George W. Bush was urged to speak up: he urged Putin to "uphold the principles of democracy."

Allegedly, Putin spoke of granting "maximum autonomy" to Chechnya at the meeting, about which The Christian Science Monitor reported no details whatsoever, except for its impressive length, three and a half hours, and its date, Monday, Sept. 6. But a week later, Putin announced radical political measures aimed at limiting - not expanding - the autonomy of Russia's 89 regions, including Chechnya. Maybe he wasn't really lying to his audience - maybe they just had a lousy translator or something.

If nothing else, the experts have sure been paying close attention to Putin's appearance:

To some of them, he looked like a man deserving some sympathy:

As for the threat of Russia carrying out "preemptive strikes ... to liquidate terrorist bases in any region of the world" - the experts have more or less agreed this wasn't something to worry about too much:

The piece wraps up with another of Anatol Lieven's quotes - a sober yet shocking assessment, which, nevertheless, takes some value off the numerous statements made by the anti-Putin, pro-human rights groups and individuals:

On Friday, Sept. 10, 2004, The Christian Science Monitor ran a story that wasn't just soft on President Putin and the FSB - it was groundlessly optimistic about the steps the Russian leadership would be likely to take after the tragedies of the past two weeks ("Russia Shapes Plan of Attack" by SCOTT PETERSON):

President Vladimir Putin refuses to meet with top Chechen separatist leaders, whom he holds responsible for a wave of terror that includes two downed passenger jets, a suicide bomb in Moscow, and the hostage crisis. But analysts say that Mr. Putin may offer far broader autonomy to Chechnya, which adds up to "de facto independence," according to American experts who took part in a 3 1/2-hour meeting with the Russian leader.

This forecast turned out to be naive, even silly: three days after this piece appeared, on Monday, Sept. 13, Putin ordered a drastic political overhaul, which, many say, is unconstitutional, would do little to prevent further terrorist attacks and would make this country resemble the Soviet Union more than ever before in the past decade or so. Even George W. Bush was urged to speak up: he urged Putin to "uphold the principles of democracy."

Allegedly, Putin spoke of granting "maximum autonomy" to Chechnya at the meeting, about which The Christian Science Monitor reported no details whatsoever, except for its impressive length, three and a half hours, and its date, Monday, Sept. 6. But a week later, Putin announced radical political measures aimed at limiting - not expanding - the autonomy of Russia's 89 regions, including Chechnya. Maybe he wasn't really lying to his audience - maybe they just had a lousy translator or something.

"He's not going to deal with a group of fighters who carry out terror attacks ... He wants to annihilate the radicals," says Fiona Hill of the Brookings Institution in Washington, who met with Putin on Monday.

Putin offered "maximum autonomy, even to the point of violating the Russian constitution," says Ms. Hill. "Does he have something down in a blueprint? I don't know. But I would say give him the benefit of the doubt for now, and see what he does."

If nothing else, the experts have sure been paying close attention to Putin's appearance:

"Certainly the veins on his skull bulge when he talks about [autonomy]," says Cliff Kupchan of the Eurasia Foundation, who also attended the Putin meeting. "He spoke about expanding the dialogue and drawing in groups that have not been included before."

To some of them, he looked like a man deserving some sympathy:

Finding those groups will not be easy. "[Putin's] been thinking hard, and looks like an alarmed man who has his back up against the wall," says Hill. "He needs help on border security, on intelligence gathering because they just don't have the capacity anymore. This is the kind of job the FSB [formerly the KGB] used to do."

As for the threat of Russia carrying out "preemptive strikes ... to liquidate terrorist bases in any region of the world" - the experts have more or less agreed this wasn't something to worry about too much:

"You always get this wave of macho talk about how we're going to do this and do that, in order to show that the military is still worth it," says Anatol Lieven, author of "Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian Power,"at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington. [...]

"They are saying that what's good for the goose is good for the gander: If you [in the US] can do it, we after such an attack can do it as well," says Mr. Lieven. "The military has obviously failed. [The Kremlin] is bankrupt, totally bankrupt of ideas." [...]

Boris Kagarlitsky, head of the Institute of Comparative Politics in Moscow, is blunter: "It is pure propaganda ... that will not make any strategic or military sense. It reminds one of a man who is in fact impotent, but wants to pretend he is still a Casanova."

The piece wraps up with another of Anatol Lieven's quotes - a sober yet shocking assessment, which, nevertheless, takes some value off the numerous statements made by the anti-Putin, pro-human rights groups and individuals:

"The Russians have not yet done everything that they could in terms of savagery," says Lieven. "All this talk of Russian abuses - most of [it is] true. But if you remember American strategy in Vietnam, or the French in Algeria, they cleared extensive areas of the countryside, put people behind barbed wire ... Anyone in those areas was by definition an enemy and shot on the spot."

"The Russians haven't done that yet," adds Lieven. "Another few attacks like this [and] the Russians could adopt much more ferocious measures."

Wednesday, September 15, 2004

My friend is writing about grieving the loss of her sister.

I've just read all of it, from the beginning to the very end.

When I was reading it, I felt it was all mine, to the tiniest detail.

When I finished reading, I realized that only the emotions were mine as well as my friend's - the memories and the experience were all hers.

Although my pain and my emotions are probably nowhere near as intense as hers, I still feel her loss is mine, too. And I feel like reading it all over again, just to live through those happy memories of being around her wonderful sister once more.

Grieving is so much about remembering all the wonderful moments.

I keep thinking about Beslan all the time - there is no place for politics in grieving. Politics may come in later, as a distraction. When there is no politics available, there is writing. And I don't know what else, how other people cope. Revenge is a distraction, too, but more often than not there is no one to take revenge on.

And when there is no grieving, there is politics.

Here are two passages from my friend's journal - but I really think nearly all of it is quoteworthy...

I've just read all of it, from the beginning to the very end.

When I was reading it, I felt it was all mine, to the tiniest detail.

When I finished reading, I realized that only the emotions were mine as well as my friend's - the memories and the experience were all hers.

Although my pain and my emotions are probably nowhere near as intense as hers, I still feel her loss is mine, too. And I feel like reading it all over again, just to live through those happy memories of being around her wonderful sister once more.

Grieving is so much about remembering all the wonderful moments.

I keep thinking about Beslan all the time - there is no place for politics in grieving. Politics may come in later, as a distraction. When there is no politics available, there is writing. And I don't know what else, how other people cope. Revenge is a distraction, too, but more often than not there is no one to take revenge on.

And when there is no grieving, there is politics.

Here are two passages from my friend's journal - but I really think nearly all of it is quoteworthy...

Tuesday, July 27, 2004

Lissa still asks for her mom. Andy still lays on his bed and cries for a few minutes before he gets up to play. Amy's son scribbles letters to Sis. "I miss Aunt ____," he says. "She can't come back from heaven, so I'll just write her a letter." They do what they need to do, then they move on with their day.

Small children express themselves naturally. Their joy, their anger, their excitement, their grief. Society has not yet told them there's an appropriate way to feel and a time limit on their emotional expressions.[...]

I have been to a therapist or two in my life for various reasons. They tell me it's good that I write it out. They say I'm healthy and don't need to see a doctor. Then they tell me it's been long enough, I shouldn't be writing about it or even thinking about it every day anymore. These same people write articles and learn from studies that state the grief process sometimes spans years. And yet they tell me one year is long enough. Don't talk about her anymore, they say. Don't give her another thought. Never mind she was your closest friend. Never mind your rock is gone. Forget about it. I know people who've grieved longer over the break-up of a relationship and it was perfectly acceptable. Expected, even, in some cases. But it's not acceptable for me to grieve the death of my sister beyond the one year mark.[...]

Monday, August 30, 2004

I often imagine myself in that car as the tires of the truck roll over the front seat. Sometimes I imagine sitting next to her. Sometimes I imagine I am her. I play it in fast forward and in slow motion, bones snapping, the smell of hot metal and blood in my nose.

Perhaps there was time for only one thought. Maybe it was realization of her coming death, concern for her children, or simply "oh fuck". Or maybe it was something absurd like "Good thing I put on clean underwear."

AFTER BESLAN: NOTES ON THE COVERAGE (2)

First, The New York Times ran a story under this headline: "Russian Rebels Had Precise Plan" (by C. J. CHIVERS and STEVEN LEE MYERS; published Sept. 6, 2004). Some people noted that it was almost like referring to the IRA guys as "British rebels."

Then, The New York Times ran this story: "Chechen Rebels Mainly Driven by Nationalism" (by C. J. CHIVERS and STEVEN LEE MYERS; published Sept. 12, 2004).

This is an interesting piece, with quite a variety of sources, ranging from the rather intangible "Russian and international officials and experts" and "three senior counterterrorism officials in Europe, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of diplomatic sensitivities" to the, allegedly, very real people like "Sergei N. Ignatchenko, chief spokesman for Russia's Federal Security Service," "Ilyas Akhmadov, a Chechen leader living in the United States," "Juan Zarate, an assistant secretary at the United States Treasury Department," "Dia Rashwan of Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo" and a number of others. The piece also contains a reference to "an unclassified report provided by the F.S.B." and a quote from Osama bin Laden's 1997 interview on CNN.

Overall, the story and the quotes do not contradict the thesis of the lead - and yet, somehow, I felt that the reporters were being unusually kind to President Putin and the FSB.

Consider this sentence about the beginning of the second Chechen war in 1999:

It isn't merely superficial (which is okay for a piece that transcends the typical recounting of the timeline of the Chechen wars) - it's weird. Do bombs drive or walk around, destroying apartment buildings? Do bombs act on their own? Even Mr. Basayev doesn't.

When the apartment buildings were blown up in mid-September 1999, roughly a month after Yeltsin unearthed Putin, it didn't occur to me to question the official version at first: maybe the Chechens indeed were behind the explosions. But very soon I realized that way too many Muscovites were talking about the FSB's role in this horror - and some of these Muscovites weren't the biggest fans of the Chechens and other ethnic minorities. So I thought, How strange - isn't it easier to blame the ones you dislike than those who are supposed to be protecting you from the ones you dislike?

In 2002, The New York Times ran a piece based on an interview with Boris Berezovsky: "Russian Says Kremlin Faked 'Terror Attacks'" (by PATRICK E. TYLER; published Feb. 1, 2002). Here's part of it, which shows that there used to be a lot more to say about those stray bombs:

Mr. Patrushev, by the way, is still the head of the FSB. The list of the bad bad terror-related things that have happened during his five-year reign is impressive (via The Moscow News; unfortunately, I haven't found an English translation of the piece about Mr. Patrushev):

The FSB has a website (in Russian); closer to the bottom of their front page I found a note from 2003, which tells us that on Sept. 11, Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of what later became known as the KGB, the predecessor of the FSB, turned 126 years old. How nice.

Back to the stray bombs: on Sept. 9, 2004, the very same New York Times published an op-ed piece, "Give the Chechens a Land of Their Own," by Richard Pipes, an emeritus professor of history at Harvard and the author of "A Concise History of the Russian Revolution." In it, Pipes does mention the ambiguity of the 1999 explosions:

It's interesting that C. J. Chivers and Steven Lee Myers do not mention General Lebed in their article. Their take on the end of the first Chechen war is this:

This is factually true, of course, but is as incomplete as the stray bombs sentence. As I said above, the purpose of this article wasn't to reproduce for the millionth time the chronology of the Chechen wars, but still, certain points in this routine background part could have been more convincing. Here's the rest of the war account, parts of which read a little bit like a translated FSB statement:

It's strange to be reminded of General Lebed now, at the time when President Putin is scaring everyone speechless with his neo-Soviet rhetoric, most likely in order to take the focus off the Beslan tragedy and the Chechnya catastrophe. What would this country be like if Lebed survived that helicopter crash in April 2002? Here's his short bio from the BBC website:

And here's a quote that ends a 1996 New York Times story by Michael Specter on the surrender of Grozny, an amazing piece that shows the magnitude of the changes that have occurred in the past eight years, not just in Russia and in the world but in the New York Times as well: Specter's "How the Chechen Guerrillas Shocked Their Russian Foes" is incomparably bolder and much more informative than many of the recent pieces, including "Chechen Rebels Mainly Driven by Nationalism."

First, The New York Times ran a story under this headline: "Russian Rebels Had Precise Plan" (by C. J. CHIVERS and STEVEN LEE MYERS; published Sept. 6, 2004). Some people noted that it was almost like referring to the IRA guys as "British rebels."

Then, The New York Times ran this story: "Chechen Rebels Mainly Driven by Nationalism" (by C. J. CHIVERS and STEVEN LEE MYERS; published Sept. 12, 2004).

MOSCOW, Sept. 11 - Chechnya's separatists have received money, men, training and ideological inspiration from international Islamic organizations, but they remain an indigenous and largely self-sustaining force motivated by nationalist more than Islamic goals, Russian and international officials and experts say.

This is an interesting piece, with quite a variety of sources, ranging from the rather intangible "Russian and international officials and experts" and "three senior counterterrorism officials in Europe, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of diplomatic sensitivities" to the, allegedly, very real people like "Sergei N. Ignatchenko, chief spokesman for Russia's Federal Security Service," "Ilyas Akhmadov, a Chechen leader living in the United States," "Juan Zarate, an assistant secretary at the United States Treasury Department," "Dia Rashwan of Al Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo" and a number of others. The piece also contains a reference to "an unclassified report provided by the F.S.B." and a quote from Osama bin Laden's 1997 interview on CNN.

Overall, the story and the quotes do not contradict the thesis of the lead - and yet, somehow, I felt that the reporters were being unusually kind to President Putin and the FSB.

Consider this sentence about the beginning of the second Chechen war in 1999:

After Mr. Basayev led a raid into Dagestan and bombs destroyed three apartment buildings in Russia, Russian forces poured into Chechnya again.

It isn't merely superficial (which is okay for a piece that transcends the typical recounting of the timeline of the Chechen wars) - it's weird. Do bombs drive or walk around, destroying apartment buildings? Do bombs act on their own? Even Mr. Basayev doesn't.

When the apartment buildings were blown up in mid-September 1999, roughly a month after Yeltsin unearthed Putin, it didn't occur to me to question the official version at first: maybe the Chechens indeed were behind the explosions. But very soon I realized that way too many Muscovites were talking about the FSB's role in this horror - and some of these Muscovites weren't the biggest fans of the Chechens and other ethnic minorities. So I thought, How strange - isn't it easier to blame the ones you dislike than those who are supposed to be protecting you from the ones you dislike?

In 2002, The New York Times ran a piece based on an interview with Boris Berezovsky: "Russian Says Kremlin Faked 'Terror Attacks'" (by PATRICK E. TYLER; published Feb. 1, 2002). Here's part of it, which shows that there used to be a lot more to say about those stray bombs: